Part Three: The Gamecocks' forgotten Atlantic Coast Conference title of 1965

How controversial sanctions and a forfeited title marked the first step towards Carolina's eventual ACC exit

(author’s note: This is the third and final installation of a three part series. Parts one and two can be accessed here and here)

Not quite four months into his dual role of athletics director and head football coach at the University of South Carolina, Paul Dietzel was a road-weary man. It was a Friday, July 29, 1966, and the forty-one-year-old Dietzel met with Joe Whitlock of The State for an interview at USC’s Roundhouse athletic offices for an article that would appear two days later.

The coach sat sock-footed in his office, feet propped into a chair. He turned off his wrist alarm reminding him to eat, and, in perhaps the most anti-Don Draper lunch ever, pulled a cheese sandwich from a brown paper bag, and poured himself a shot of milk.

“Honestly, I’ll be glad when we get down to practicing football,” Dietzel confided to Whitlock as he stared into the mid-distance, thinking about the herculean task he had undertaken at South Carolina. “It’s all this outside business that consumes so much time.”

The new coach estimated he had driven 10,000 miles, criss-crossing the state during his first few months at USC. Wherever he went - chamber of commerce breakfasts, booster-club luncheons, or simply meeting people on street corners from Beaufort to Spartanburg, and Myrtle Beach to North Augusta, Dietzel was selling an idea.

“We have a lot of dreams and they aren’t idle dreams. They are definite plans and I know we can do them. Almost everything we want to do, all the plans we have point to one fact,” Dietzel said. “We need support. Without support, nothing we are planning will transpire… I keep getting the feeling I’ve seen this show before.”

Indeed, he had not just seen the show, but had been the primary actor in a similar plea for support a decade earlier at LSU. When the thirty-one-year-old Dietzel took on his first head coaching opportunity in Baton Rogue, he encountered road blocks to success that mirrored those he now faced in Columbia. “They had never sold over 2,000 season tickets,” Dietzel said of LSU’s season ticket sales before his arrival in 1955. “In 1958, we stopped season ticket sales at 35,000, and LSU has never sold less than that since.”

Contrasting LSU with South Carolina, Dietzel singled out Carolina Stadium as a liability. “…it’s 26,000 plus seats smaller. Yet the student body here is 2,000 people larger, and the metropolitan area is more than twice the size Baton Rouge was when I was there.”

Dietzel had spent his first hundred days sizing up challenges, devising plans, shaking hands, and evangelizing through the hot summer months like a hillbilly preacher on a tent revival circuit.

But winning hearts and minds wasn’t the only business Dietzel dealt with during those early months.

ACC sanctions vacate wins, removes ‘65 conference title

The same Friday of Dietzel’s interview with The State, the ACC announced the results of its months-long investigation into Marvin Bass’s program and the Gamecocks’ 1965 football team.

Conference commissioner Jim Weaver announced that USC had violated ACC regulations by providing illegal aid to at least one freshman football player and two varsity players. As a result, Weaver ordered that all games in which the varsity members participated be forfeited to the opposing teams. South Carolina’s 4-2 conference record - good enough for a share of the ACC title with Duke - would now become 0-6.

The penalty stripped the Gamecocks of its lone ACC football championship. To add insult to injury, the ‘65 conference crown passed to rival Clemson, along with NC State, whose records both improved to 5-2. Duke, through no fault of its own, lost its share of the ACC crown, falling to third place with their 4-2 record.

Both NC State’s Earl Edwards and Clemson’s Frank Howard expressed regret and discomfort over their newly-awarded shares of the ACC title. “All I know is the score of our game will always read the same, 17-16, South Carolina’s favor,” Howard said.

Weaver did not announce the names of the players involved, but noted that they would be banned from future participation in the ACC.

Dietzel, who had conducted his own internal investigation, confirmed the report and also declined to announce the names of the athletes involved. “I don’t think any good purpose can be served by disclosing the boys’ names,” Dietzel said.

Reached for comment in Montreal, former coach Marvin Bass said he didn’t believe Dietzel’s investigation turned up anything he had not already told the commissioner himself before departing South Carolina.

“If Coach Dietzel wanted to go in with a 1-9 record (instead of 5-5) so he couldn’t possibly do anything but improve this season, I wish him luck. I hope he can live in good faith and look people in the eye. If I were going to conduct an investigation, I would at least have had the courtesy to contact the guy who was there before me,” Bass said.

Bass later apologized for his remarks, and took full responsibility for the situation.

For his part in the matter, Dietzel told reporters, “I didn’t come here to become an investigator. I was told to look into the matter and report my findings to the commissioner’s office and to the university, and I did what I was told. I reported my findings, and Weaver told me that the information I had was the same information he had. So here, I don’t think I did very much to aid the investigation,” before adding, “I hate to see this happen to a bunch of kids who went out there and played their guts out to win a championship.”

One university official who spoke with The State’s Herman Helms on the condition of anonymity noted the aid provided to the three players “was meal money and text books. The amount was very small, no more than $75 or $100 per player.”

Of the two varsity players, one was a reserve, the other a starter in a few games. One of them had graduated, the other left school when he could not meet academic requirements. The freshman player was still attending USC, but was no longer a member of the football program. None of the athletes were scholastically eligible to receive aid from the university, the report revealed.

The largely insignificant contribution of the players and the small dollar amount of aid did not erase the transgressions, Helms opined, noting the University did not “deserve sympathy for wrongdoing.” Like many others though, Helms did take exception to the second part of Weaver’s four-part declaration of penalties.

It is because of this flagrant disregard for constituted authority, Weaver’s ruling began, that any athlete at the University of South Carolina whose eligibility is questioned be withheld from participation unless and until it is established to the complete satisfaction of the conference that there has been no violation in each individual case.

The ruling was tantamount to “guilty before innocent,” and cast a wide net of suspicion across not just football, but all of South Carolina’s athletic programs.

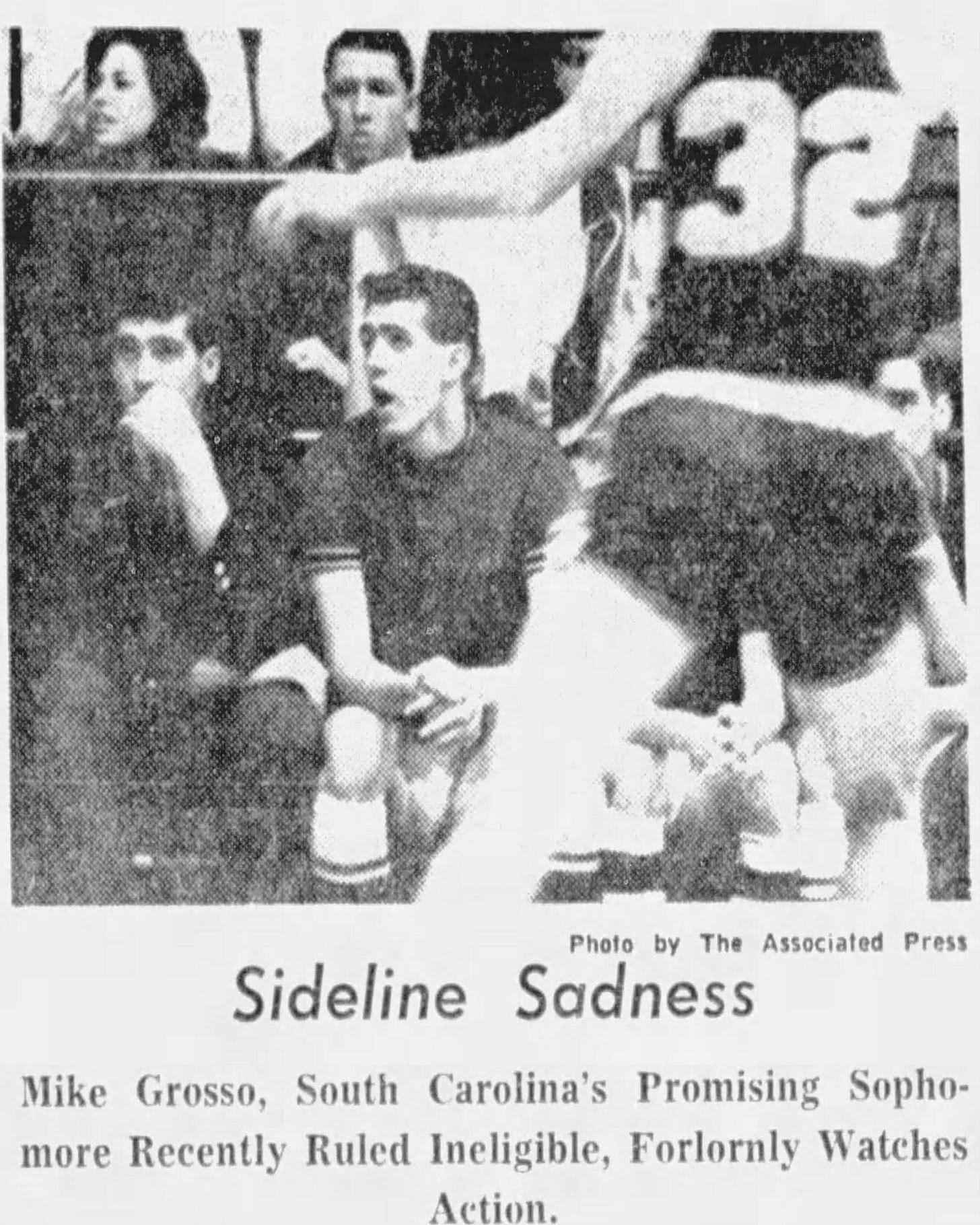

Soon to be caught up in that net was Frank McGuire’s prized freshman, Mike Grosso.

The ACC scholarship rule then in place stipulated that no athlete could receive financial assistance unless he achieved a score of 800 on his college board (SAT) examination. Non-scholarship athletes could participate with a minimum score of 750, however, and it was through this loophole that Grosso landed at South Carolina, courtesy of some help from family.

Grosso’s uncles, who owned a bar back home in New Jersey, agreed to cover the freshman’s tuition until he could qualify for a scholarship. Grosso had never scored 750, the minimum for competition, during his attempts at the SAT as a high school senior. He subsequently retook the SAT exam on the campus of the University of South Carolina, in July, 1966, scoring a 706 - still short of qualifying for participation.

On a second attempt in September, 1965, also on the USC campus, Grosso scored 789, qualifying him for participation in the ACC. He was dominant on South Carolina’s 1965-66 freshman team, averaging 22.7 points and 26 rebounds per game. One account noted Grosso pulled down 41 rebounds in a game versus Duke.

The Grosso situation did not sit well with Duke’s athletics director Eddie Cameron, who harbored a simmering personal feud with McGuire going back to the latter’s UNC days. To compound matters, Duke’s basketball coach Vic Bubas had tried unsuccessfully to lure Grosso to Durham. Bubas and McGuire also feuded in the aftermath of a wild brawl between UNC’s Larry Brown and Duke’s Art Heyman in 1961, during McGuire’s final season at North Carolina.

Cameron threatened to boycott Duke’s games with South Carolina when Grosso moved up to varsity the next year, while goading the ACC to launch a sprawling investigation into Grosso’s recruitment and eligibility.

At Cameron’s further prompting, the conference closed the SAT loophole, updating the standard for participation, not just a scholarship, to 800. Though that change did not apply to Grosso retroactively, the ACC used continued questions around his recruitment and eligibility to snare the young man in Commissioner Weaver’s “wide net” ruling, regarding any South Carolina athlete “…whose eligibility is questioned.”

By the fall of 1966, the ongoing ACC investigation cast a shadow of doubt over the much-anticipated start of Grosso’s varsity career, then just weeks away.

“The Off-Court Uproar in Dixie”

On Friday, October 28, 1966, USC President Thomas Jones, assistant athletics director George Terry, and McGuire attended a meeting of the ACC executive committee at the Triangle Motel, located at Raleigh-Durham Airport (Dietzel was traveling with his team for a matchup at Maryland).

After meeting for nearly four hours, executive committee head Ralph Fadum advised the USC contingent that the committee saw no cause to overturn Commissioner Weaver’s earlier decision to disqualify Grosso. Neither Weaver nor Fadum would divulge why Grosso was ruled ineligible.

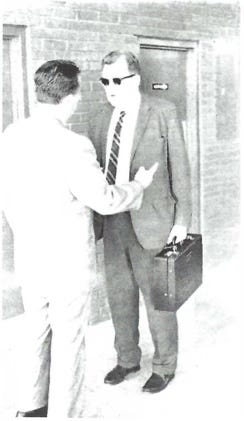

Mark Mulvoy of Sports Illustrated, in a November 7, 1966 article titled “The Off-Court Uproar in Dixie,” noted that McGuire had to be physically restrained by Jones following the ruling, and a dramatic photo that ran with the piece showed McGuire confronting Weaver (sunglasses on, briefcase in hand, trying his best to get the hell out of there).

In public remarks over the coming days, McGuire called ACC officials “skunks,” and “rats,” noting, “they have forced me into the gutter with them.” The remarks drew sharp criticism from coaches, athletics directors, and presidents within the conference.

Some South Carolina boosters and alumni called for a withdrawal from the conference. They saw the ruling as clear evidence of political dominance by the “Big Four” North Carolina schools within the ACC. The conference leaders involved in the Grosso drama, ACC commissioner Weaver of Wake Forest, ACC basketball committee chairman Cameron of Duke, and executive committee head Fadum of NC State, made that point inarguable.

For his part, McGuire saw the Grosso decision as a personal vendetta against him by enemies accumulated over a decade of bitter ACC battles as head coach of both UNC and South Carolina.

“They are not after Grosso, they are after me,” McGuire told Mulvoy of Sports Illustrated.

As Mulvoy closed his article, he noted USC’s coming appeal, and ominously, that the NCAA was also investigating the Grosso affair. His ending was prescient. “Whatever the outcome, it has engendered enough bitterness in the ACC to last for years.”

The ACC’s ruling, though not divulged to McGuire and Jones during that contentious executive committee meeting, hinged on an obscure, albeit useful technicality. The Educational Testing Service (ETS) of Princeton, New Jersey, was the governing body that prepared and admitted the board exam. ETS guidelines dictated that it would accept and recognize only one institutionally administered college board exam for each student. Grosso’s first attempt at the SAT in Columbia resulted in a 706 score. It was that score, not Grosso’s second score of 789, that was sent to the ACC offices and represented the only official score, according to ETS rules.

McGuire’s disparagement of ACC officials in the days after the executive committee meeting did little to bolster whatever slim hopes USC harbored for an appeal. Those hopes received a final blow in January, 1967, when the NCAA announced the results of its own investigation into USC’S football and basketball programs.

The NCAA determined that Grosso’s expenses had been paid by “a corporation upon which the student athlete was neither naturally nor legally dependent.” The “corporation” in question referenced the bar owned by Grosso’s uncles and the tuition assistance provided by them. The NCAA dealt harsh penalties to both programs, banning post-season tournaments or bowl games for two years. In the embryonic days of television broadcasts, USC was also banned from appearing in televised games during the same period.

Grosso, who McGuire once boasted would bring championships to South Carolina, never played a varsity game for the Gamecocks. He transferred to Louisville, where he received a scholarship and played behind the great Wes Unseld during his first season before starting his final two. He averaged 18.6 points and 13.9 rebounds during his senior season of 1970, and went onto a brief, injury-plagued career in the ABA.

Speaking with David Cloninger of Charleston’s Post and Courier in October, 2022, Grosso said it took counseling and a lot of time to get past what happened in those ACC boardrooms during the summer and fall of 1966.

“I had a void, it took me 20 years to get over it. I was just wandering, lost, without a real vision as to what was ahead.” He says meeting his wife, Barbara, helped all that. “She provided that vision. All that anger and ugliness melted away. She was my Coach McGuire. She made me whole again.”

USC basketball legend Jack Thompson calls Grosso, “…the best damned basketball player I was ever blessed to step onto the hardwood with. We all knew we were with greatness ‘beyond category’ at that moment. Through years of trials and tribulations, and just life itself, the thought remains so vivid, as if it were just yesterday.”

An exit set in motion

The University of South Carolina was never supposed to challenge for ACC supremacy. Certainly that was not the design of the “Big Four” schools who constituted the governing nucleus of conference hierarchy.

An editorial from The State just days before USC announced its conference exit in March, 1971 summed up the situation from South Carolina’s perspective:

The Atlantic Coast Conference was formed by the four North Carolina members for the benefit of the North Carolina members. They needed USC, Clemson, Maryland and Virginia (a late joiner) to fill out a decent conference. But the outsiders were supposed to be step-children, to be seen and not heard

It was becoming clear by the mid-60’s that the University of South Carolina would no longer accept a supporting role in the conference it helped found in 1953. From the hiring of basketball coach Frank McGuire in 1964, to its first share of an ACC football title in November, 1965, to an upset of third-ranked Duke in basketball a few days later, to the hiring of athletics director and head football coach Paul Dietzel in 1966, the South Carolina Gamecocks were ascendant. With championship coaches and elevated recruiting came renewed fan interest, increased funding, and an undeniable kinetic momentum.

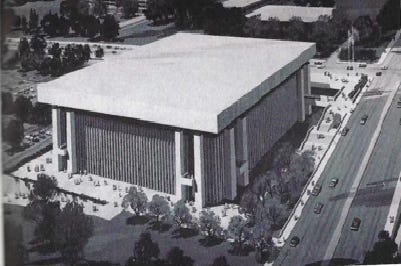

By 1965, plans were advancing for a new basketball arena, which upon its completion in 1968 would be the finest facility of its kind in the ACC, and in the entire Southeast. Following closely behind, an upgraded football stadium, and a vastly improved baseball facility, along with state-of-the-art athletics dorms, training and dining facilities.

A step-child no more, South Carolina claimed an outright ACC football championship in 1969, an undefeated regular-season basketball championship in 1970, and an ACC tournament title in 1971.

By early 1971, just as the Gamecocks reached their zenith of competitiveness in the ACC, Carolina’s conference exit seemed all but guaranteed. The ground was salted, the earth scorched, and collegiality among sister institutions lay broken beyond repair for years to come. By that time, the driving force behind the Gamecocks’ approaching ACC exit was Dietzel.

USC’s athletics director and head football coach (a vastly troubling conflict of interest in hindsight) had grown weary of watching South Carolina high school stars go on to stellar careers at Big 8 and Big 10 schools because they could not qualify for a scholarship under ACC regulations.

On March 29, 1971, USC’s board of trustees announced that the university would withdraw the university’s ACC membership effective August 15 of that year - a timetable later accelerated to June 30.1

Many have argued that South Carolina made a historic blunder when it stepped away from the Atlantic Coast Conference with no apparent plan for conference affiliation elsewhere in June, 1971. Many more argue it was for the best.

Carolina’s struggles during the “wilderness” years of the 1970’s and 80’s, most poignantly the decline of its once powerful men’s basketball program, supports the former argument. USC’s current lofty perch of lucrative stability above the churning chaos of conference realignment lends credence to the latter. Debate over the wisdom or foolhardiness of South Carolina’s ACC exit will continue among fans and pundits for years to come.

One thing seems clear though. The Gamecocks’ share of the 1965 ACC football title, combined with the ascendancy of its basketball program under McGuire - a brash New Yorker many in the staid ACC hierarchy loved to hate - roiled the status quo. It lit a fire among “Big Four” officials who looked to tamp down any budding conference insurgency outside of the Old North State.

Other insurgencies followed, with noted successes by Clemson, Virginia and Maryland in the 70’s and 80’s. But from 1965 through 1971, the Fighting Gamecocks of South Carolina led the first rebellion, and the most fearsome.

Sources:

Hunter, Jim and Cole, Bob: ACC rules Gamecocks must forfeit title, Columbia Record, July 29, 1966.

Denberg, Jeff: Violation of ACC regulations takes away Gamecocks only football championship, The State, July 30, 1966.

Helms, Herman: ‘The only thing he could do’, The State, July 30, 1966.

Denberg, Jeff: Dietzel followed orders. The State, July 30, 1966.

Whitlock, Joe: ‘My only concern is the future’, The State, July 31, 1966.

Mark Mulvoy: The off-court uproar in Dixie, Sports Illustrated, November 7, 1966.

Sumner, Jim: When South Carolina and Duke truly hated each other, Duke Basketball Report, June 8, 2020.

Cloninger, David: Before GG Jackson, the Gamecocks had another top recruit who never played a game, Post and Courier, October 13, 2022.

Just over a year after Carolina’s ACC exit, on August 7, 1972, a federal judge struck down the ACC’s embattled 800 SAT rule, calling it “arbitrary and capricious,” and “not based on valid reasonsoning.” By this time, there was no clear path back to ACC membership for the Gamecocks, who would not join an all-sports conference again until accepting an invitation to join the SEC on September 5, 1990. The Gamecocks officially joined the SEC July 1, 1991, exactly twenty years and one day after exiting the ACC.

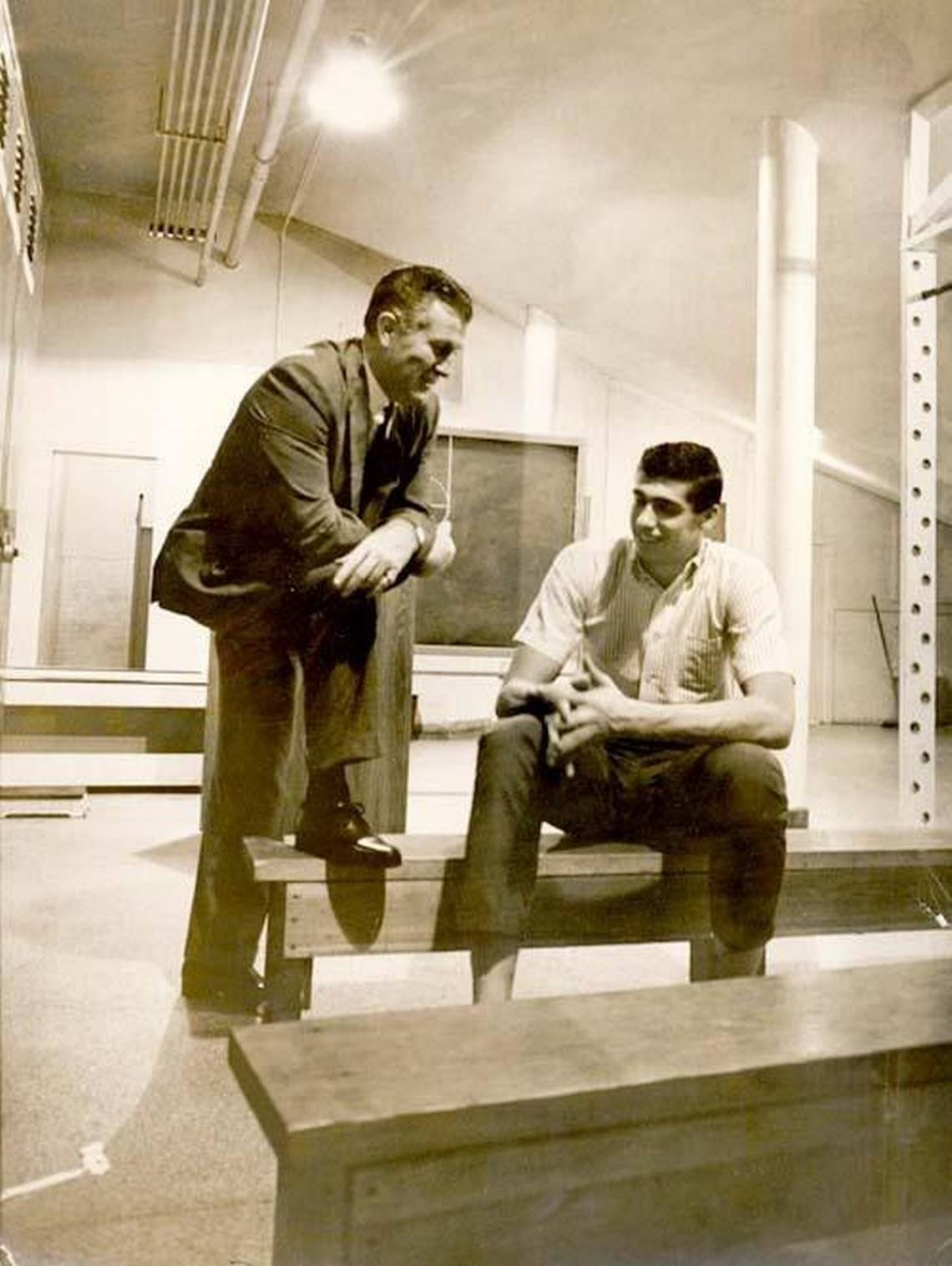

Alan, I’m enjoying this tremendously. I am sure you’re aware of what I’m about to say, but the lack of support from the USC administration on the Grosso affair upset coach McGuire so much that he was very close to taking the Sixers job after they acquired Wilt. It was only the difficulty and moving Frankie and his determination to still stick it to Eddie Cameron and Jim Weaver that kept him from doing it. Also, the fact of the university turned around and rolled and left the ACC when Dietzel had trouble with the 800 rule, just increased his anger at what leaving the conference did to his program. Also, in Coach McGuire‘s home in West Columbia, where he lived the last few years of his life, he had two pictures on the wall in his living room. One was a sketch of a fighting gamecock. The other was that picture of Coach and Mike Grosso taken in the Fieldhouse locker room. When we won the ACC tournament, Roche as captain accepted the trophy With Coach McGuire standing right behind him. Roche said “we accept this trophy in memory of Mrs. McGuire and on behalf of Mike Grosso”