Part One: The Gamecocks' forgotten Atlantic Coast Conference title of 1965

How controversial sanctions and a forfeited title marked the first step toward Carolina's eventual ACC exit

When South Carolina met Clemson in the final game of the 1965 season, it was before a home crowd of 44,500, the greatest assemblage of spectators in the sixty-year history of the rivalry. For the first time in the storied Palmetto State series, Carolina and Clemson were playing with a conference title on the line.

The Gamecocks had been picked between sixth and last in all of the pre-season ACC forecasts, but out-performed expectations in league play, carrying a 3-2 conference record into the contest.1 Clemson, meanwhile, had played a full conference slate and carried a 4-2 ACC record into the final game.

Clear skies and temperatures in the mid-60s set a grand backdrop for the troubled family reunion, as a great many partisans sporting garnet, and a few thousand others clad in orange, settled in among the old bowl of time-worn wooden bleachers at Carolina Stadium.

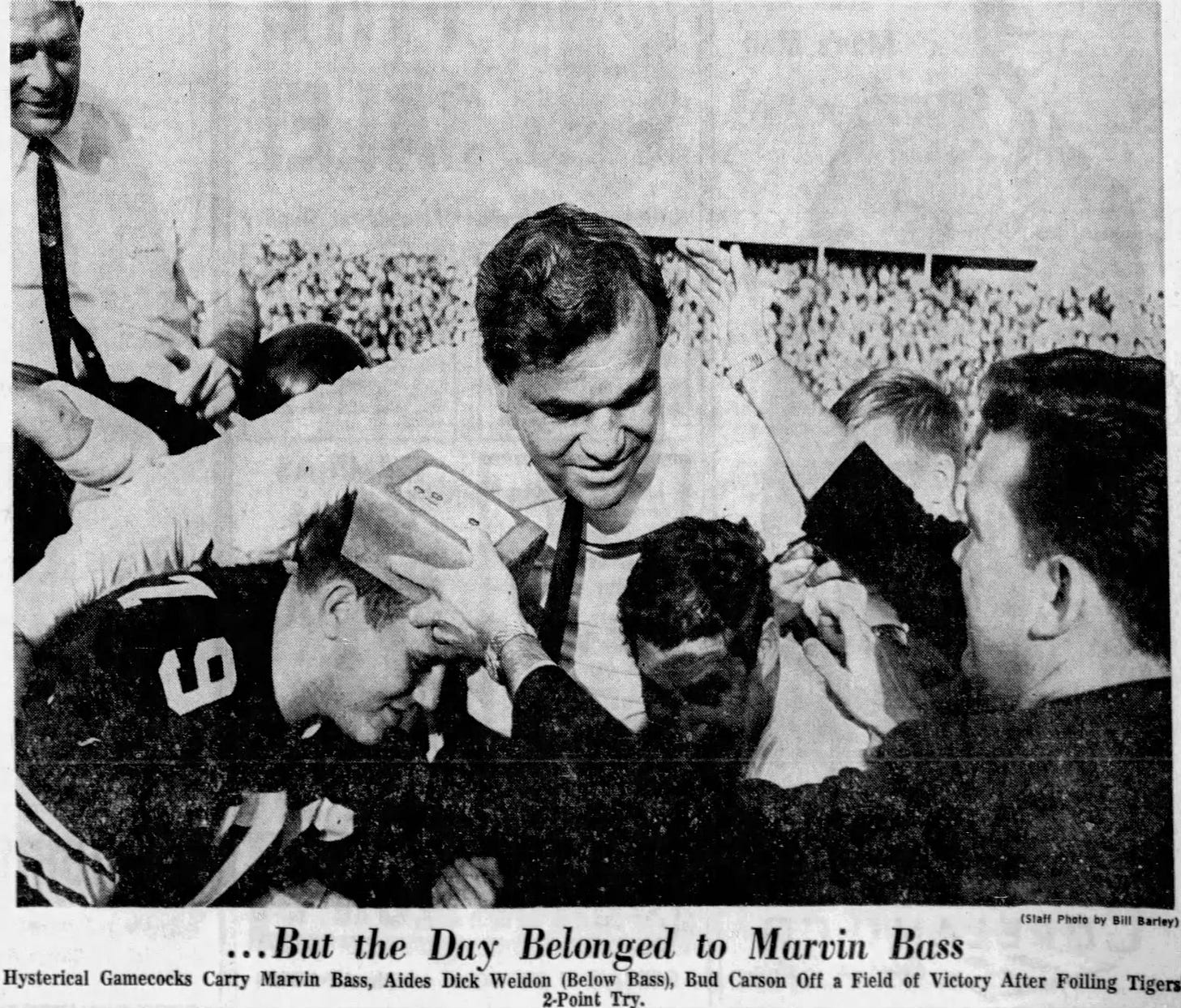

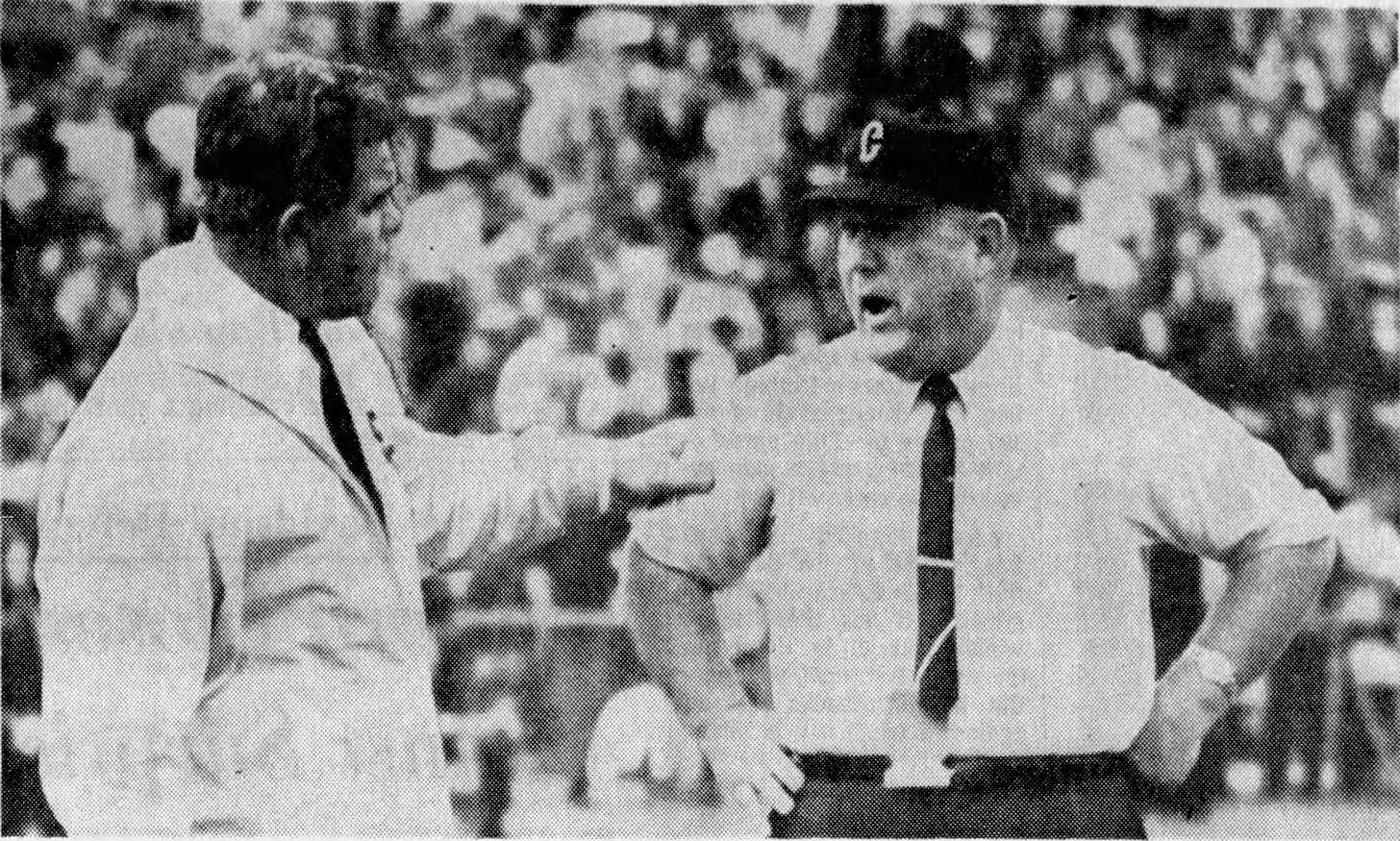

Clemson held the all-time series lead with 36 victories to Carolina’s 23. The meeting marked the fifth between Carolina’s head coach Marvin Bass, and Clemson’s Frank Howard, with each coach claiming two wins. Oddsmakers had installed the Gamecocks as a three-point favorite, though odds held little sway in this emotion-filled rivalry series.

The Tigers dominated play through most of the first half, and led 10-0 before a momentum-shifting 50-yard strike from USC quarterback Mike Fair to his favorite target, receiver J.R. Wilburn. The big play set up a short rushing touchdown from tailback Jule Smith to pull the Gamecocks within three after the Jimmy Poole extra point.

A 31-yard field goal by Poole knotted it at 10-10 near the five-minute mark of the third quarter. When the Gamecock defense held on Clemson’s ensuing possession, Fair directed his offense 55 yards on nine plays, setting up a seven yard scamper from halfback Bobby Harris for the go-ahead score, propelling the Gamecocks to a 17-10 lead.

A Bobby Bryant interception at the USC seven-yard-line stopped Clemson momentum mid-way through the final period, but the resilient Tigers capitalized on their final opportunity, manufacturing a stellar 73-yard drive in the waning minutes. Facing a fourth-down inside the Gamecock one-yard-line, Clemson quarterback Thomas Ray dropped back and fired a touchdown strike to flanker Phil Rogers for the late score, trimming the Tiger deficit to one, 17-16.

With time running out, Clemson lined up for a point-after attempt, apparently content with a tie, though Bass’s Gamecocks and 44,500 fans suspected a fake. The stadium throbbed with nervous energy as fans ringed the sidelines, hands on knees like coiled springs.

The ball snapped to holder and second-string quarterback Jimmy Addison who executed the anticipated fake, rolling to his left, spotting fullback Bo Ruffner in the corner of the end zone. Addison fired a rope to Ruffner, but Gamecock linebacker Bob Gunnels stuck out a long arm in the nick of time, swatting the ball harmlessly to the turf as time expired.

Gunnel’s timely play preserved the Gamecock win, and more substantially, provided Carolina a share of its first-ever conference championship. Pandemonium ensued, as fans rushed the field and jubilant players carried Bass and assistants on an impromptu victory ride.

Speaking with reporters after the game, senior fullback Phil Bronson summed up the feelings of many,

“I can’t think of a better way to end a college career than winning a part of a championship, especially since we at South Carolina have never won a championship before. I’m just glad I could help do something for Coach Bass before I finished.”

The normally stoic Bass, speaking with The State’s Joe Whitlock after the game let down his guard, revealing his thoughts on the state of the program, and uncharacteristically venting frustrations over external negativity impacting the team.

“I think we got a head start today when we won a share of the ACC championship. I don’t think I’ve ever worked at a better place than the University of South Carolina, and I’ve never worked with better people,” Bass noted, before his reflections took a darker turn;

“I’ve had to eat a lot of crow here and I’ve had to swallow my pride because the people who don’t count thrive on spreading rumors that aren’t’ true. I’d like to cuss out some people,” he said, “but I’ve always kept my mouth shut. There have been some things I’ve wanted to say, but I let them pass because I’m proud of this University and it doesn’t deserve the treatment some people seem to want to give it.”

Bass continued, “South Carolina can be good in every sport. That’s what it deserves. But show me a school that hasn’t won anything since 1894 that has had the support we’ve had here. The school has never had a chance. There has been a plot to disrupt the athletic setup. It’s impossible to imagine the number of rumors that have made their way back to me that have obviously been designed to tear down the team.

“Someday this place is going to blossom and get what it deserves and when it does it’s really going to be something to see.”

A plot to disrupt the athletic setup? This seemed ominous, and oddly off-key in light of what Bass called his greatest win as a head coach. The events of the next several months would take Carolina from the heights of that championship moment through a bizarre chain of events that seem almost hard to fathom nearly sixty years later.

A strange and dramatic offseason

Just over two weeks later, Frank McGuire’s basketball Gamecocks claimed the first of many milestone victories in a thrilling 73-71 win over third-ranked Duke at Carolina Fieldhouse.2

Senior Sports Editor Herman Helms of The State opined,

McGuire’s Monday miracle, coming so close on the heels of the Gamecocks’ first football championship in 71 years points to an inescapable fact. USC, long an athletic punching bag, can fight back now.

People were hysterical (after USC’s Duke win) because in this victory there was a promise that someday - not this season of course - but someday not too far away, this sort of thing will become commonplace.

Helms was prescient about McGuire’s program. After all, playing on the freshman team that December was the nation’s second-ranked recruit in six-foot-eight center Mike Grosso from Raritan, New Jersey. The big man would average nearly 23 points and 26 rebounds on the season. Fans salivated over the prospect of Grosso joining the varsity squad a year later, where McGuire’s first recruiting class of Jack Thompson, Frank Standard, Skip Harlicka, Skip Kickey, and holdover Gary Gregor were already making waves in the vaunted ACC.

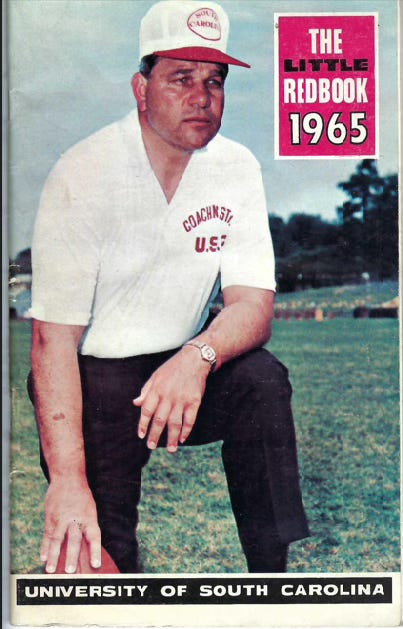

Additional football success seemed a foregone conclusion as well, with championship hardware already secured and Bass seemingly hitting his stride going into year six at the helm.

In late January, 1966, defensive coordinator Bud Carson left the Gamecock program to join Bobby Dodd’s Georgia Tech staff. Dick Bestwick, another defensive coach, had resigned days earlier for an assistant job at Pittsburgh.3

On February 21, Bass hired former Connecticut assistant Lou Holtz to work with the defensive secondary, noting that Holtz would replace Bud Carson on the staff. “He is an energetic young coach with a bright future,” Bass noted of Holtz. “He should do fine with us.”

A month later, with still no hint of the seismic things to come, Bass and staff kicked off spring practice. Jim Hunter of the Columbia Record, waxed poetic in a March 22 article:

The muscular young lad walked slowly across the ruffled turf in a twilight of bangs and bruises. His heart flowed out in the sweet smell of early spring, the nostalgic scent of sweat and grass that is football pulled out of the locker room again. He is a raw, rising sophomore, Earl Hunter, and the spring was to be an awesome awakening for a young guy who loves a game of physical action.

An injury to his collar bone ended his early spring training Monday afternoon, and the grass and dirt turned momentarily sour in the twilight of afternoon.

“Its a time you find out who the football players are,” Marvin Bass said of spring football drills.

Just a week later, and still in the midst of spring practice, Coach Marvin Bass would unexpectedly resign his position at USC to pursue a lucrative head coaching offer with the Montreal Beavers of the nascent Continental Football League.

Bass’s move would usher in the Paul Dietzel era, which began amid an ongoing ACC investigation into the eligibility of three players from the 1965 varsity and freshmen squads.

Coming next week in Part Two - A controversial ACC ruling strips USC of its only football title and ensnares Frank McGuire’s prized recruit, propelling the Gamecocks toward their eventual conference exit five years later.

For reasons that are unclear, not every team played a full conference slate in 1965. USC did not play North Carolina, while Duke did not play Maryland. Clemson and NC State, meanwhile, each played a full conference schedule.

Host Chris Horn takes us back to that magical 1965 upset of Duke in the “Beat Dook!” edition of his excellent Remembering the Days podcast. Hear reminiscences from Gamecock great Jack Thompson and former USC student Joe Wachter, who attended the game.

Carson would succeed Dodd as head coach at Georgia Tech, and went on to much success as defensive coordinator with the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers, where he was instrumental in developing the famed “Steel Curtain” defense. Carson’s defense would propel the Steelers to Super Bowl championships in 1975 and ‘76.

Bestwick later joined Carson’s staff at Georgia Tech before being named head coach at the University of Virginia (1976-81). He eventually entered athletics administration, and would serve an abbreviated term as athletics director at South Carolina in 1988, during a turbulent period narrated by the Tommy Chaikin steroids scandal.

Loved the article. It's always good to beat MooU - even when we go back in time!!

Thanks for another great article on Gamecock history.

Keep up the good work.

Mom