“Sure, he has a weakness. I noticed that he doesn’t dribble too well with his left foot.”

- Norm Sloan

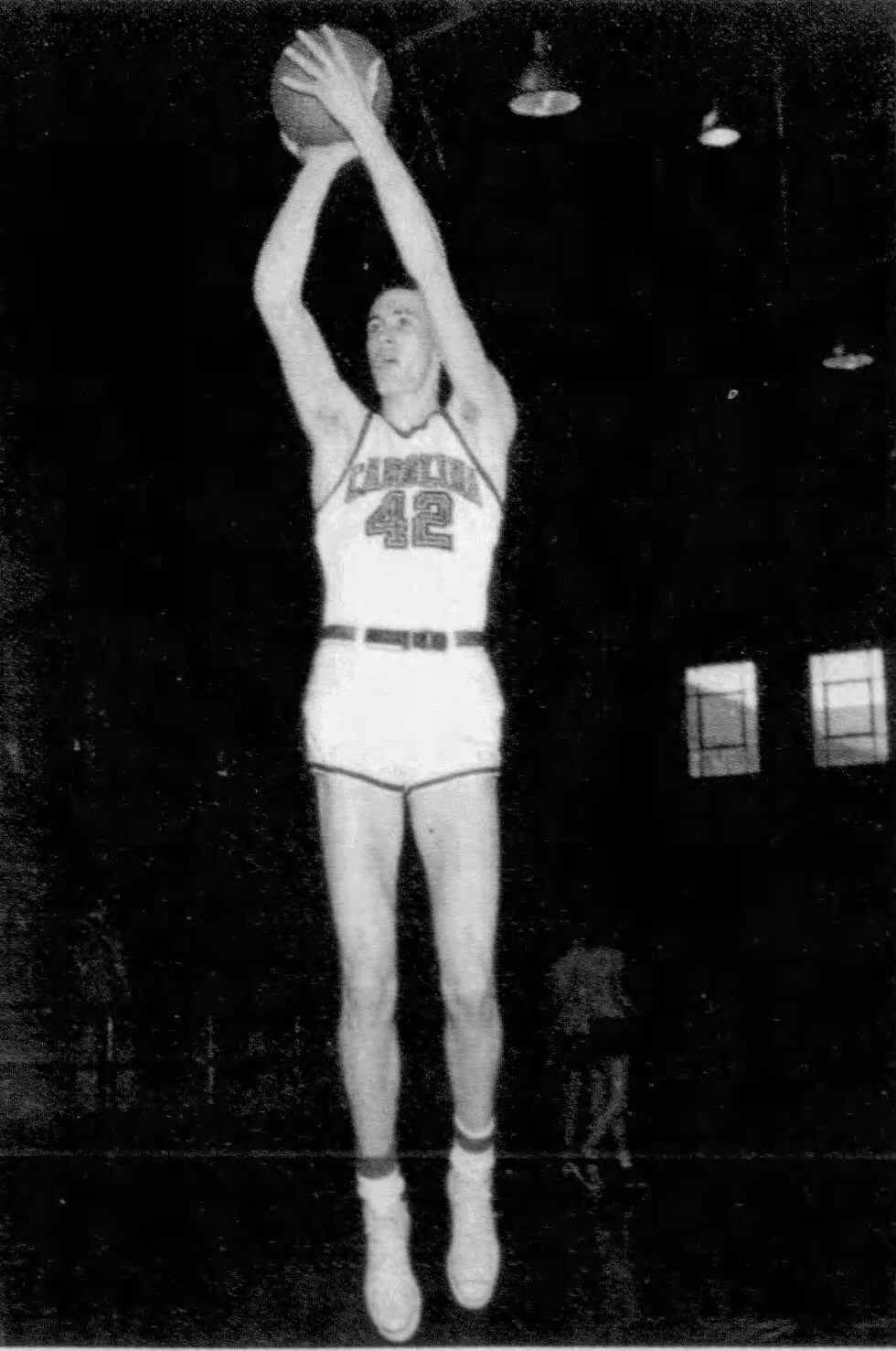

For decades, Grady Wallace’s number 42 jersey has hung among the rafters of Carolina Coliseum and Colonial Life Arena. For most fans too young to remember, his banner brings to mind sepia-toned set shots and dusty field houses. It hangs beside the more familiar names and numbers of Roche, and Joyce, and English, and McKie, a whisper of greatness from the shadowlands of pre-McGuire times.

But spend some time perusing the Gamecock basketball record book, and his greatness comes into sharp focus. His name is ubiquitous and inescapable. Some sixty-six years after his final game in the Garnet & Black, Wallace owns records which will likely never be broken.

He still owns program marks for career and single-season scoring average (28.0 and 31.3 respectively), points scored in a season (906), two-year scoring total (1,456), field goals made in a season (334), and free throws scored in a season (234).

Wallace accomplished these superlatives over the course of just two seasons, in a time well before the three-point line. Consider that he also averaged 32.4 points per game as a sophomore at Pikeville (KY) Junior College before landing in Columbia.

To ponder what he would have accomplished over a four-year career with a three-point line is simply mind-boggling.

Wallace was South Carolina’s first All-American and All-ACC designee, and the first Gamecock to lead the ACC in scoring and rebounding. His number 42 jersey was the first retired by the program, and only the second in any sport.

Moreover, he remains the only NCAA season scoring champion to come out of the ACC’s original eight schools. In doing so, Wallace out-dueled two of the games most prolific legends in Kansas’ Wilt Chamberlain and Seattle’s Elgin Baylor for scoring supremacy.

Scoring’s Silent Partner

“The devil put the coal in the ground; devil put the coal in the ground; double-dog dare you to follow men down; devil put the coal in the ground.” - Steve Earl

Wallace hailed from the hardscrabble mining town of Mare Creek in the coal-haunted hill country of Eastern Kentucky. He entered the world in the midst of the Great Depression on January 20, 1934, the second of two children to Rufus and Sadie Wallace. Rufus was a coal miner, who later found work with the Kentucky highway department when black lung forced him above ground for good. Sadie was a homemaker.

Entertainment options for teenagers in 1940’s Eastern Kentucky were few, and tended to revolve around either hunting or basketball. Wallace chose the latter.

Janet Wallace, Grady’s widow and wife of 47 years, recalls Wallace came from humble means, but was a perfectionist in anything he set his mind to. She relayed a story passed on from Wallace’s mother,

“She told me he hung a basketball goal on his bedroom wall, and would lay in bed at night shooting baskets,” Janet says, laughing. “She would fall to sleep to the ‘kathunk, kathunk’ of a basketball rattling through the hoop and hitting the floor.”

Basketball proved to be Wallace’s ticket out of the coal mines. A six-foot-four forward, he excelled at Betsy Layne High School, and hoped to catch the attention of Adolph Rupp at the University of Kentucky.

Perhaps owing to his slight build at only 140 pounds, that attention never materialized. He enrolled instead at nearby Pikeville Junior College (now the University of Pikeville), where he played two seasons. During his sophomore year he led the nation in scoring at the junior college level with a 32.4 points-per-game (ppg) average.

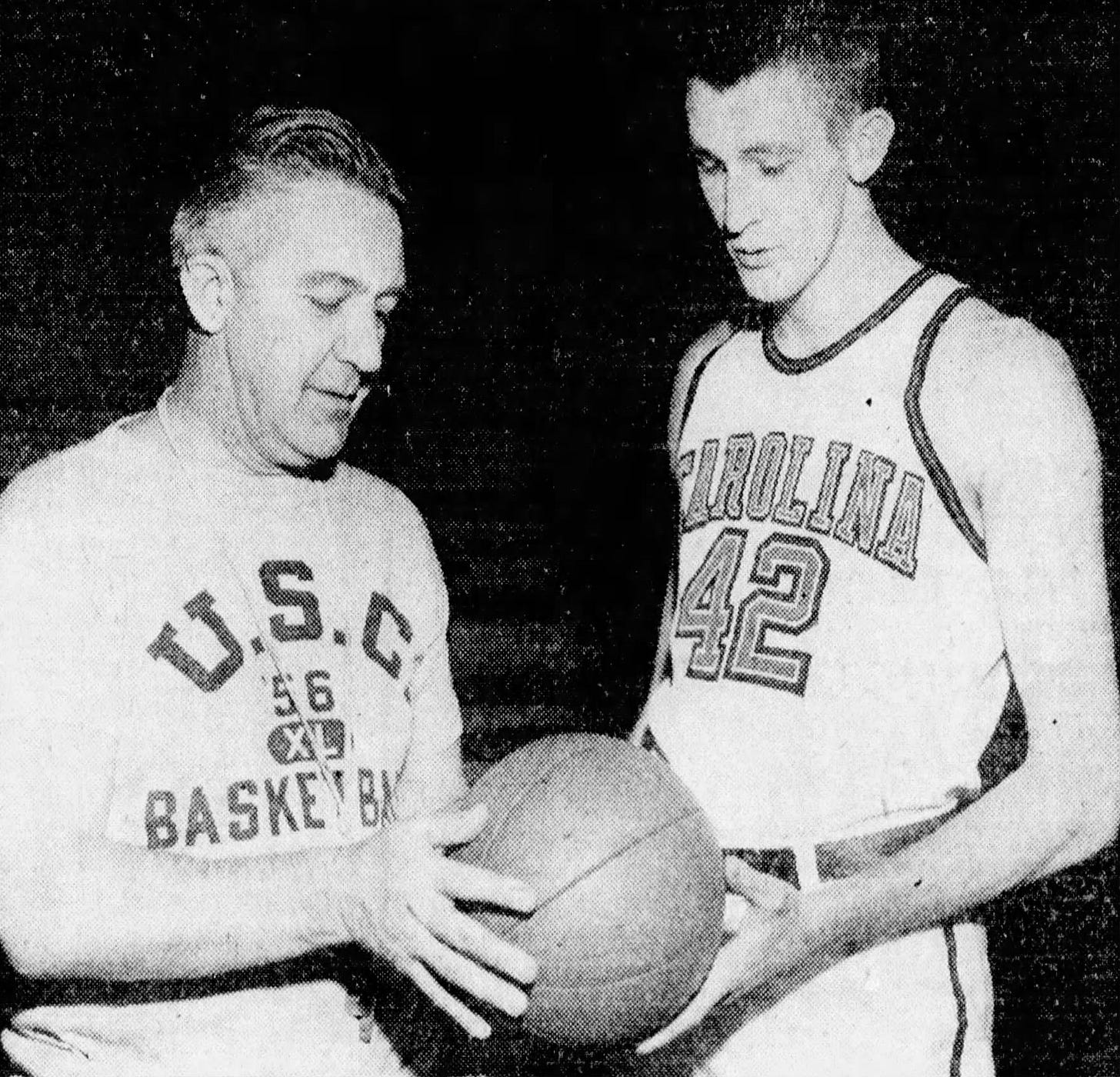

Following that 1954-55 season, the University of South Carolina’s Frank Johnson lured Pikeville coach Walt Hambrick to Columbia to serve as Gamecock assistant. Five Pikeville players, including Wallace followed Hambrick south to USC.

Wallace was an immediate star for the Gamecocks, finishing with a 23.9 ppg average during his junior season of 1955-56, good for second in the ACC after North Carolina’s Len Rosenbluth.

Though he was an elite scorer, he still struggled to gain the weight he needed to steel himself against the rough and tumble life of an Atlantic Coast Conference forward. “A couple of doctors checked Grady,” Hambrick told The State’s Jake Penland in 1957. “They tried to put weight on him. One of them even talked about deworming him.”

He was finally able to pack on an additional seventeen pounds before his senior season, and excitement grew around Columbia to see what the quiet Kentuckian could accomplish in his final collegiate campaign.

1956-57 - A season to remember

Wallace delivered on fan expectations throughout his senior season. He set a program record for points in a game (54) versus Georgia at Athens in December, and set a Carolina Field House record with 44 against Virginia in February. After the Virginia game, talk turned to Wallace’s scoring average, which had risen to over 29 ppg, good for second in the country behind Kansas’ seven-foot center Wilt Chamberlain.

Could Wallace overtake Chamberlain for the NCAA scoring crown? It didn’t seem an unreasonable notion, considering the scoring title for the prior four seasons belonged to two South Carolina-based players in Furman’s Frank Selvy (1953 & ‘54) and Darrell Floyd (1955 & ‘56).

On Valentine’s Day, 1956, Furman’s Floyd and Carolina’s Wallace went head to head in a classic at Carolina Field House. Floyd got the better of Wallace in the scoring column that night, pouring in 40 to Wallace’s 25, but the Gamecocks prevailed in a 109-97 thriller.

Wallace looked to continue the Palmetto State’s national scoring dominance in 1957.

The Gamecocks were winning too, carrying a 14-11 overall record into their final home game versus Clemson on March 2, 1957.

Wallace had overtaken Chamberlain by this time, with a better-than 30 ppg average. The double attraction of Wallace’s final home game and a Carolina-Clemson matchup resulted in a massive turnout. About an hour before tipoff a big crowd lined up three abreast, stretching over a block from the field house.

As tipoff approached it became obvious that university officials would be unable to accommodate all of the would-be spectators. Police were brought in to guard the field house entrance. Every inch of space was taken inside the 3,200-seat facility, and several hundred more than that jammed inside before police finally bolted the doors.

Overflow crowds were commonplace during Wallace’s two seasons, prompting much discussion about the need for a larger venue at Carolina. It would take over a decade for those talks to come to fruition.

The field house was raucous in anticipation of another big night from Wallace. Clemson, led by coach Press Maravich, had won the season’s earlier meeting, 79-71 at the Tigers’ Fike Field House, which ACC coaches frequently referred to as “a snake pit,” and “an insane asylum,” for its spartan environs and hostile crowds.

Clemson held it close in Columbia, trailing only 13-11 with fourteen minutes remaining in the first half, but as Penland of The State wrote, Frank Johnson’s “doggoned determined Gameroosters,” broke it open with an eleven-point run and Clemson never threatened again.

With Carolina up comfortably, Johnson pulled Wallace with a minute left, allowing the senior to bask in the praise of a rousing ovation. Quickly though, Johnson realized Wallace had tied his own 44-point home scoring mark and still had a chance to break the record. He quickly sent Wallace back onto the floor.

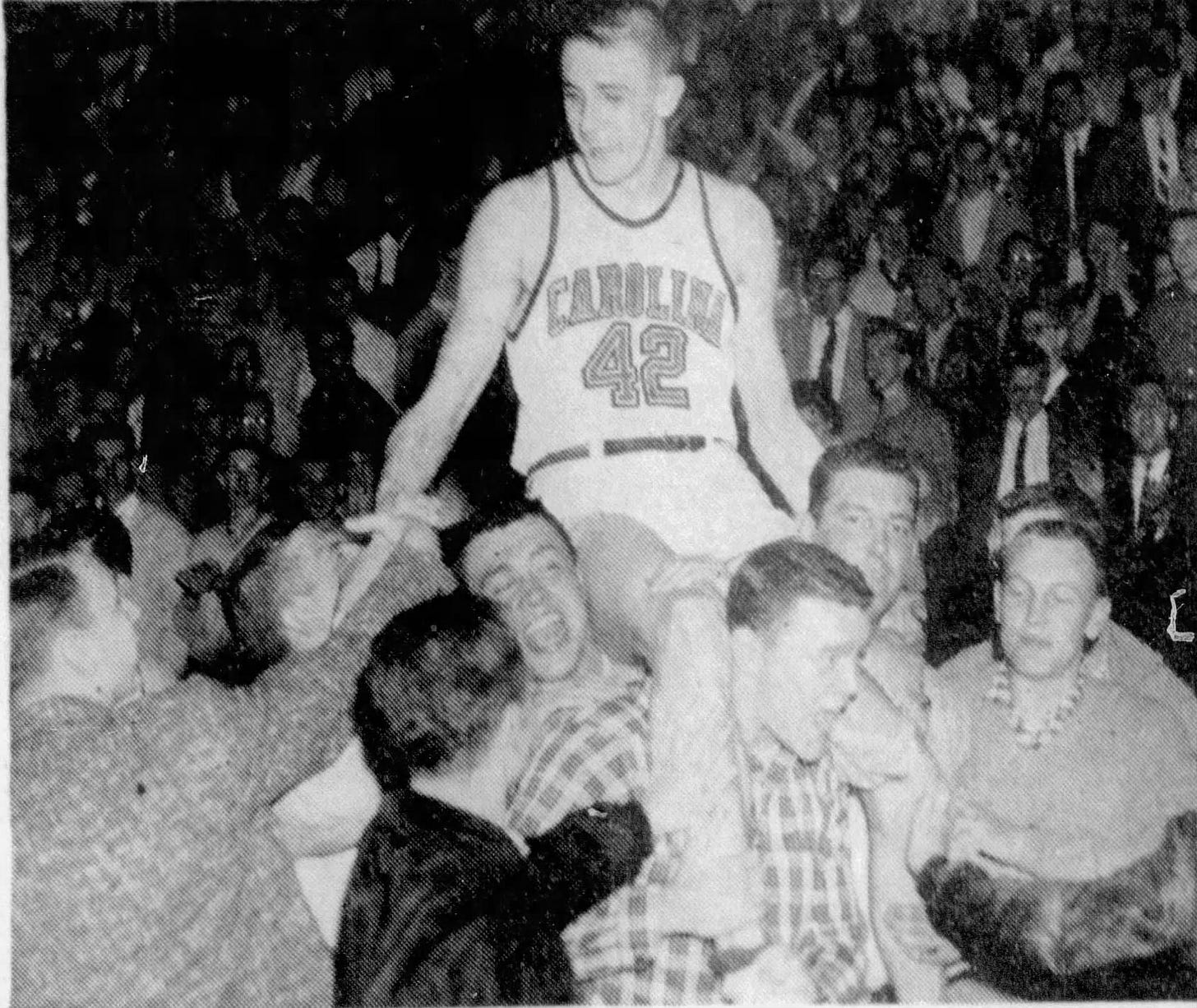

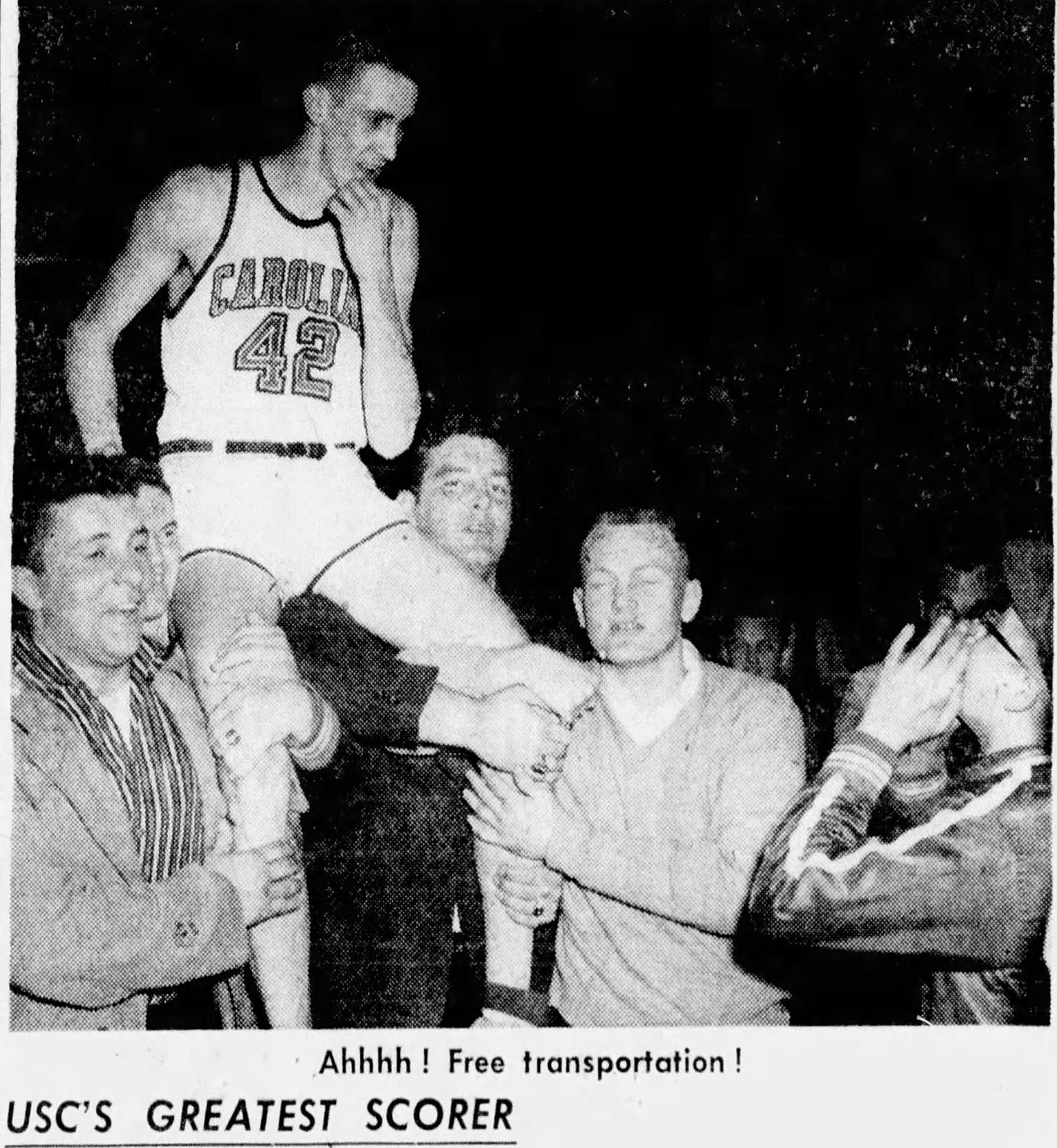

Though regulation expired before he could manager another bucket, the overflow crowd chanted, “Wallace, Wallace,” as the buzzer sounded on a 113-85 Gamecock win, and the conquering senior received a hero’s ride atop the shoulders of his fellow students.

An “almost unbelievable rally”

Carolina entered the 1957 Atlantic Coast Conference basketball tournament at Raleigh’s Reynolds Coliseum with an 0-3 record in the event since the conference’s founding in 1953. Despite a winning regular-season ledger (15-11), South Carolina had taken its lumps in conference play, compiling a less than impressive 5-9 record.

Nobody gave the Gamecocks much of a chance for any greater success in the ACC tournament, as Carolina was matched with Duke in their March 7 opening round game. The Blue Devils owned a twelve-game winning streak over the Gamecocks, going back to 1951, when the two schools were members of the Southern Conference.

Following the anticipated script, the Gamecocks found themselves down 28-14 midway through the first half. As the game wore on though, Wallace and the scrappy Gamecocks began to heat up, closing the gap to 79-72 with 3:49 remaining. Duke employed a slowdown approach in response, and with no shot clock, Carolina was forced to foul.

With Duke still up 81-75 in the final minute, Wallace scored on a layup to pull within four. He then converted two free throws following a Duke turnover, trimming the Blue Devil lead to two.

With twenty seconds remaining, Wallace drove the lane for a tying layup, and was fouled on the play. His conversion put the Gamecocks up 82-81, and Wallace iced the game with two more free throws at the five-second mark, giving Carolina the final margin, 84-81.

Wallace had scored the Gamecocks final 14 points, including nine in the final minute.

He ended with 41, pushing his season average to 31.37, all but securing the national scoring title. Moreover, the victory marked South Carolina’s first in the ACC tournament, and the first post-season tournament success of any kind since knocking off Duke in the Southern Conference tournament a decade earlier.

Duke coach Hal Bradley was less than generous in assessing the Gamecocks’ winning effort, telling reporters, “We missed the layups and the free throws that could have iced the game for us. That and only that beat us.”

Bob Fulton, the Gamecocks’ longtime radio voice reminisced with Bob Spear of The State about of Wallace’s performance from that opening round game in a 2006 article. “Basically, Grady stood in the corner and burned the nets down.”

The Gamecocks rode the momentum of its Duke win to a second-consecutive tournament upset, this time over Maryland the following day. The Gamecocks won 74-64, with all five starters scoring in double figures. Wallace scored 31 and set a new two-game scoring record in the ACC tournament. Three consecutive steals by USC guards Cookie Pericola and Bobby McCoy led to six points within a minute in the fourth quarter, securing the unlikely Gamecock win.

A final ride

The Gamecocks found themselves an unlikely challenger for the ACC tournament title versus Frank McGuire’s undefeated and #1-ranked UNC Tar Heels. South Carolina had played UNC well in the regular season, losing in overtime in Columbia, and losing a close one at Chapel Hill after leading by six at one point in the second half.

The Gamecocks stood between McGuire’s Tar Heels and their date with destiny in the NCAA tournament.

UNC’s superior depth carried the day however, as McGuire substituted freely throughout the game, while Johnson leaned mostly on his exhausted starting five. The Gamecocks stayed close through ten minutes, down only 23-19, but UNC delivered a devastating blow, scoring 23 unanswered points to go up 50-23 at halftime. Though the Gamecocks showed grit, outscoring the Tar Heels in the second half, the deficit was too great to overcome and UNC won handily, 95-75.

Wallace’s 100 points in three tournament games set a new ACC record, but that provided meager comfort to the Gamecock legend as he slipped off his garnet jersey for the final time.

In two seasons, Wallace scored 1,456 points for a career average of 28.0. To put that into perspective, the great John Roche is second at 22.5. No player in the three-point era has come close. His single season total of 906 and 31.24 ppg average in 1956-57 is still a program record and remains second in ACC history.

Wallace also led the ACC in rebounding that season.

With no invitation to post-season play for the Gamecocks, Wallace would have to wait for the results of the NCAA tournament to see if Kansas’ Wilt Chamberlain could catch him for the scoring title. Chamberlain’s Jay Hawks made it all the way to the finals, losing in three overtimes to McGuire’s Tar Heels. Reflecting years later, Chamberlain called the championship game loss to UNC his most painful moment of his career.

The seven-footer needed 67 points in the final to overtake Wallace for the scoring championship. He ended with 23.

Wallace received first-team All-America recognition from two of the three wire services, United Press International and International News Service, and second-team recognition from the Associated Press. He received first-team All-ACC honors; the first such recognition in program history.

He went on to play for the East All-Star squad, coached by McGuire in Kanas City on March 25th, along with UNC’s Rosenbluth and Mississippi’s Joe Gibbon. Wallace scored twelve in a loss to the West All-stars, led by Seattle’s Elgin Baylor.

The NBA’s Boston Celtics drafted Wallace in 1957, but he opted instead to play two seasons for the Industrial League’s Phillips 66’ers in the days before professional basketball became a path to riches.

A legend endures

The University of South Carolina retired Wallace’s #42 jersey, and he was inducted into the South Carolina Athletics Hall of Fame in 1968.

Wallace went on to a successful career with the South Carolina Department of Probation, Pardon and Parole, ultimately retiring as Commissioner. In his spare time, he coached Columbia’s Cardinal Newman High School for nine seasons, winning two state championships.

He died of heart failure at the age of 72 in 2006, leaving behind his wife, Janet, a daughter Leigh Ann, and a son, Thomas, as well as three grandchildren. Beyond that, he left an indelible mark on legions of teammates, players, coaches, co-workers, friends, and family.

Following the 1957 ACC championship game, Don Barton of the Columbia Record wrote of Wallace,

“Thus exits Grady Wallace, a quiet Kentuckian who gave new birth to basketball interest in Columbia, and laid down a challenge for his Gamecock ancestry. For in years to come whenever a bright new star appears on the school’s basketball horizon, they’ll always bring up the question, “Well, how would you compare him with Grady Wallace?”

His words still ring true today.

Many thanks to Mrs. Janet Wallace for taking the time to speak with me for this piece.

I heard Joe Quigg tell a story about the 1957 game in Chapel Hill between the Gamecocks and the Tar Heels. Quigg said that he “held” Grady Wallace to 17 points, and after the game Grady told him it was the best anyone had played him defensively all year. He said Coach McGuire patted him on the back and said “that’s something to be proud of, Joe.”