A fine christening under heavy skies

From the archives: Williams-Brice Stadium debuted as Columbia Municipal Stadium on October 6, 1934

“Performing on a soaked field, under heavy skies that often wept, the Gamecocks played alert football, making and taking the breaks, to beat the Flying Squadron, 22 to 6, while a great crowd, cut short by the weather but formidable at that, forgot the discomforts of the rain, and saw an interesting, clean-cut battle.” - October 7, 1934 commentary from The State on the inaugural game at Columbia Municipal Stadium

The 1934 season dawned late by modern standards, with the opening game between Carolina’s Gamecocks and the Erskine Flying Fleet taking place in Columbia on September 29. It was the final game at the old wooden grandstands of Melton Field, Carolina’s football home between 1926 and that opening game of ‘34.1

“Carolina opens season versus Erskine Seceders,” a newspaper headline proclaimed, citing an older nickname for Erskine’s athletic teams. A Greenville sports writer, Carter “Scoop” Latimer, commented on Erskine’s passing strategy following a 1929 football game, noting Erskine looked like a “flying fleet,” and the name stuck. The student body soon voted to adopt it as their official nickname, however “Seceders” hung around in the popular lexicon for years after.2

Gamecock coach Billy Laval, in his seventh and final season at the helm for Carolina, had led his program to one of the more successful eras in program history, including a 3-0 Southern Conference ledger in 1933. An article in The State on the morning of that first game noted Carolina had won a share of the conference title in ‘33, however Duke had gone 4-0 and was officially recognized as the conference champion. Notably, Carolina was also riding a rare three-game win streak over their arch rival Clemson Tigers coming into the 1934 season, and expectations were high in Columbia for continued success.

There was further excitement for the 1934 season because of a sparkling new home stadium set to host Carolina’s second game versus Virginia Military Institute (VMI) a week later.

Carolina handily defeated Erskine 25-0 in the opener, and all attention turned to the dedication of their new venue.

A series of newspaper articles during the week leading up to the VMI game examined all facets of the new stadium. “New Stadium Eliminates Sun From Players’ Eyes,” proclaimed one. Most on-campus stadiums across the country were shoehorned into relatively small parcels of whatever land might be available amongst other campus buildings. The size of the lot obtained for Carolina’s new stadium, over twenty acres located approximately two miles south of campus, permitted engineers to locate the playing field in any direction they desired. The northwest to southeast orientation of the new field was designed to lessen the effects of sun in player’s eyes.

The framework of the stadium was entirely clad in steel, painted battleship grey. Seats were comprised of two cypress boards, with spacing eleven inches wide - commodious for lean Depression-era sports fans, but decidedly tight by the standards of today’s ever widening populace. Rest rooms were located under the stands, along with two dressing rooms, each containing six showers with hot and cold water - luxuries at the time. The north and south ends of the stadium were enclosed by board fences, designed to be temporary in nature, and easily replaceable by additional stands for future expansions.

“Long work by interested people”

Efforts to secure a new stadium for the university had been led by George Bell Timmerman, Sr of Batesburg, former president of the Carolina Alumni Association, USC Law graduate, and federal judge. As the Great Depression deepened, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs offered a lifeline for municipal projects across the country, providing financing through programs such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and labor through the Works Progress Administration.

Land for the new stadium was purchased by friends of the university who gave $100 apiece after the owner, Mrs. Thomas Taylor, agreed to sell for a significantly reduced price. The Taylor family had owned vast swaths of land along the Congaree River for generations, including the land which became the planned city of Columbia, when South Carolina’s capitol moved from Charleston to the Midlands in 1786.

The stadium property was deeded to the City of Columbia so that bonds could be issued, as the University could not take on such bonds by matter of law. The city later deeded the facility to the University in 1935, when it was rechristened Carolina Stadium.

Built at a cost of $82,000 ($1.93 million adjusted), the stadium was designed by Columbia architects Lafaye and Lafaye, and engineers Sumwalt and Rowe. The steel contractor was Virginia Bridge & Iron Co, and woodwork was provided by W.A. Crary and Son of Columbia. The stands were built with a crescent shape, designed to ensure that every spectator could see every play from any of the 18,200 seats.

Due to insufficient appropriations, the stadium was built with “efficiency, durability, and capacity as the dominating factors of construction,” according to designers. Eventual upgrades were anticipated to include enclosure of the exposed steel work visible from the exterior of the stands, with high brick walls arranged as series of archways with high ornamental iron gates. Many of those decorative flourishes would eventually occur, though for the better part of nine decades the stadium maintained a spartan, industrial feel, even through numerous expansions.

Civic Pride on display

The State noted of the opening game, there would be a continuous round of “delightful and attractive events,” beginning at 3pm, with the game following.

“You can see another game in the stadium later, but there will be only one dedication, only one ‘first game,’ and those who do not join the merry throng for the VMI-Carolina contest will always regret it.”

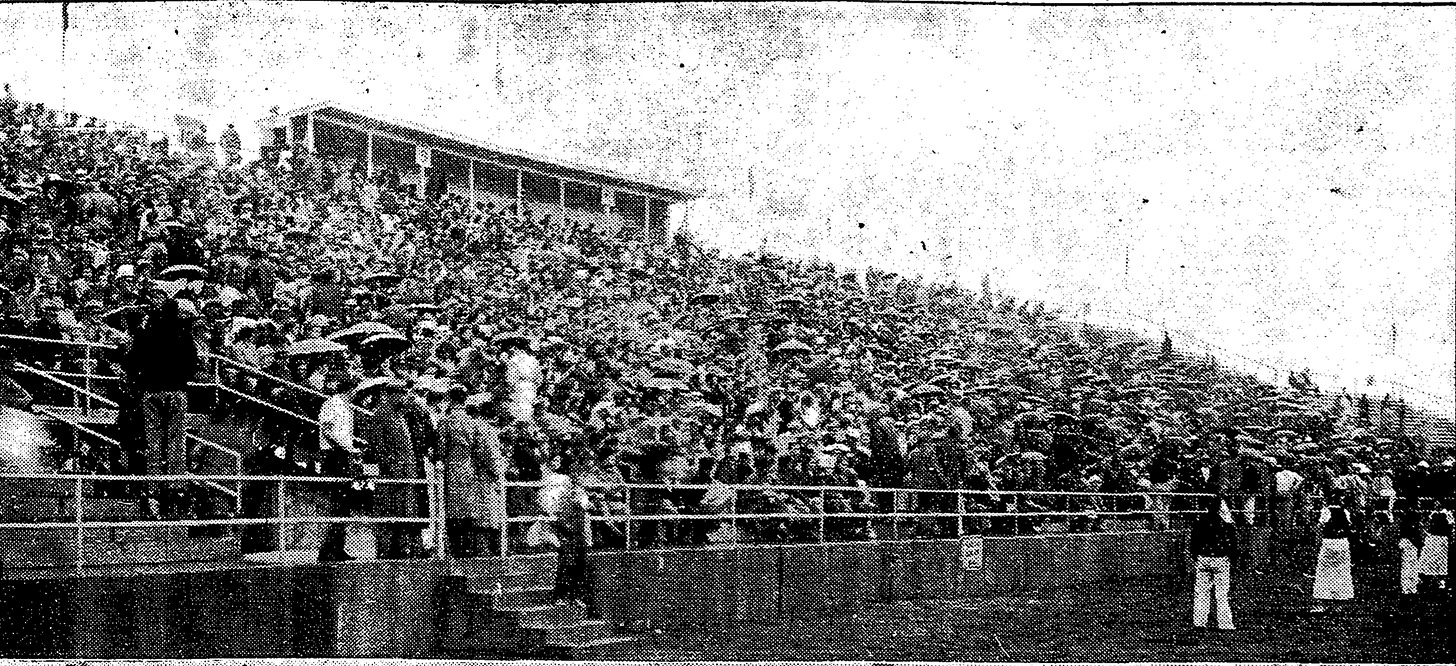

Saturday, October 6 dawned grey and drizzly with an unpromising forecast for the opening festivities. Reports noted the dedication ceremony would carry forth, rain or shine.

By 3pm, skies grew darker and a fine rain which had been intermittent all day began to fall steadily. The rain, according to reports, “in no way dampened the enthusiasm of the crowd present, and the several features of the program were followed with closest interest.” Around 10,000 spectators filed into the stadium, the rain suppressing what would have been a likely sellout in more agreeable weather.

At the appointed time, the various dignitaries and university brass assembled at the north end of the field. The Columbia High School band marched in their white uniforms down the gridiron, followed close behind by the Carolina band in its garnet, black and white regalia. Next came the American Legion drum and bugle corps in their blue and gold finery, sporting chrome helmets. An assemblage of distinguished guests followed, including South Carolina Governor Ibra C. Blackwood, Governor-elect Olin D. Johnston, and Columbia Mayor L.B. Owens, among others.3

The vaguely militaristic sounds of battle drum and bugle heralded the dedication ceremony as the high school band went to one side of the flag pole, the Carolina band to the other, while the drum corps split ranks, cleaving the way for distinguished guests to walk through, along with “nine lovely girls” who each took a part in the christening ceremony, all carrying handsome bouquets of dahlias arranged in the colors of the University of South Carolina, and of the Virginia Military Institute. The Carolina band played the alma mater as the crowd rose, umbrellas dotting the stands.

Timmerman approached the podium for his dedication speech.

“For years while I was president of the alumni association, I entertained the hope that the university would have a stadium for its athletic activities comparable with those enjoyed by its peers, and in keeping with its surroundings, its dignity and importance.”

Mayor Owens rose next, and after brief remarks of acceptance, hoisted Old Glory to the top of the flag pole, “which caught in a breeze and was thrown out to full length,” according to reporting. As the flag ascended, the Carolina band played the Star Spangled Banner and at it’s conclusion, a young coed, Ms. Wooding of Victoria, Virginia, dashed a bottle of champagne against the flag pole in a great celebratory spray. And at that, the ceremony concluded.

Hardly had the field been cleared, when the low drone of an airplane could heard through grey skies, and from out of the clouds came P.P. Parish, Jr, operator of the Parish Flying Service at nearby Owens Field. He circled the field in his biplane, flying north over Columbia, then doubling back, making a low pass over the stadium.

Parish dropped from his open cockpit a football carrying the colors of USC and VMI. The toss fell adroitly near the center of the field, as the plane banked and swooped back over the stands. A goggled and leather helmeted Parish, his scarf flapping behind, gave the crowd a snappy wave as he disappeared among the low clouds.

A few moments later, whistles blew and the game was on in the new municipal stadium, “the realization of a dream long entertained by lovers of sports.”

Carolina won that first game convincingly, 22-6 over the visitors to move to 2-0 on the season. Scoring was highlighted by a blocked VMI punt by right end Bob Johnson which was recovered in the end zone for a touchdown by left end John Rowland.

The Gamecocks went 2-2 at their new home that season, beating VMI and Virginia Tech, and losing to both Clemson and William and Mary en route to a 5-4 season (2-3 SoCon).

But beyond the wins and losses of 1934, Columbia Municipal Stadium marked a triumph of partnership between a city and a university. It stands as a monument to civic-minded men and women who, even while toiling under the burdens of unprecedented economic strife, chose to engage in the hard work of collective problem solving, of principled and visionary action over the easy petulance of political gridlock, and of optimism over fear.

Old stadiums, it seems, hold lessons for us all.

Melton Field was located south of the Horseshoe, along Greene Street, at the site now occupied by the Russel House Student Union building.

Abbeville, South Carolina, located 95 miles northwest of Columbia along the Georgia line, and approximately 12 miles south of the Erskine campus in the Abbeville County town of Due West, is known the "Birthplace and Deathbed of the Confederacy.” On what is now known as Secession Hill, the meeting which launched the state's secession from the Union took place on Nov. 22, 1860. Five years later in 1865, Jefferson Davis and his cabinet decided to dissolve the Confederacy at the Burt-Stark Mansion, a stately home right off from Abbeville's Historic Court Square. abbevillecitysc.com

Columbia Mayor L.B. Owens is the namesake of Columbia’s first municipal airfield, Owens Field.

On a hot afternoon in August 1964----the 'Great Man' pulled tight the heavy mahogany door to his office, at some place Frank Standard had called the Roundhouse on Rosewood Dr.. Sorry, I never heard of it or had seen it before because I just barely got my ( passing ) summer school grades from Archbishop Molloy--up in Queens, N.Y.--so, it was too late in the year for a 'prospect' visit'. But I was about to meet the great Frank J. McGuire, who was in the process of driving out to Columbia Metropolitan Airport, in his brand new, black Cadillac El Dorado, to pick up Frank Standard and I----Standard had been here before--I hadn't--it was only by chance Standard and I wound up on the same Eastern Airlines jet out of La Guardia Airport that afternoon. So "Big Frank" gets there --late--looks at me and says, " You must be Jack Thompson!" Yes, I told him "I am!" Ignominious would be an understatement, as to our first tete e' tete. Oh, wait, this is about the Columbia Municipal Stadium opening almost 30 full years earlier.

McGuire decided to take us to lunch at some place, as it turned out right across from the football stadium. After lunch he walks us across the street and into this beautiful football field----at the time called The Carolina Stadium. My eyes are wide open--I am so impressed--wow, it don't get any better than this--I have arrived--big time college sports---and the 'Kid from the Candy Store' in Brooklyn. I love the place. This was a love affair that has lasted until this day in 2025. to me it was majestic--Saturday afternoons spent watching my friends, like Dan Reeves Marty Rosen, Larry Gill, Pete Di Vinere----play UNC, Wake Forest, Clemson-and others---where my dreams came true--I will never forget seeing The Columbia Municipal Stadium for that first time on a HOT AUGUST AFTERNOON ---escorted by the Great Man himself---my own personal "Field of Dreams!

Thank you so much, Alan. Hadn't thought of it for quite some time.

Wow! What a read!!!

Thank you for posting this.