Part 2 - Gamecock great Jimmy Foster opens up about his life, career

Originally published on Gamecock Central, February 28, 2021

It was the first day of spring, March 21, 1983, and a capacity crowd descended upon the Carolina Coliseum for a second round NIT matchup between the 21-8 Gamecocks and a 23-10 Virginia Tech squad featuring high-scoring freshman Dell Curry.

The early-evening air was cool, perfumed by jasmine and dogwood bloom, which yielded to the aroma of popcorn as fans pressed into the arena, handing tickets to genial doormen in garnet blazers. Sneakers squeaked on the arena’s Tartan floor during warm-ups, and the pep band was in fine form, playing “Go Carolina” and “Step to the Rear.”

A professor from the university’s school of music delivered stirring renditions of the Star Spangled Banner and USC alma mater, charging the crowd. The retired jerseys of John Roche and Kevin Joyce and Alex English swayed from the massive rafters above. Electricity surged through the arena in anticipation of tip-off.

The Gamecocks rode an excellent defensive effort to overcome poor shooting, and escaped with a 75-68 win over the Hokies, securing what was then the Gamecocks’ deepest run ever in a postseason tournament.

Talking with reporters during post-game interviews, Jimmy Foster looked as if he had gone 15 rounds with Marvin Hagler, having taken an inadvertent kick to the face when he drew a charge from Tech’s Perry Young just before halftime.

The kick resulted in a nasty gash above his left eye, requiring stitches to close. Foster suspects he also suffered a concussion which went undiagnosed in a time before concussion protocol. Despite the injury, Foster battled valiantly through blurred vision, collecting 10 rebounds in the second half and finishing with 11 points. It was classic Foster grit.

Despite two home victories in the tournament and strong attendance, the NIT awarded third round hosting privileges to Wake Forest, not at their usual home court, the 8,200-seat Winston-Salem War Memorial Coliseum, but in the 15,000-seat Greensboro Coliseum.

It would be South Carolina’s first visit to that venue since the program’s lone ACC tournament championship win over UNC 12 years earlier. It was only the third match-up versus a North Carolina-based ACC foe since departing the conference in 1971.

Foster was advised by team doctors to sit out the Wake game due to his eye injury, but he says the opportunity to play in front of extended family in Greensboro, including his grandfather, was too much to pass up.

The homecoming was spoiled by poor team shooting in South Carolina’s worst performance of the season, connecting on 26 of their 77 shots for a dismal 33.8 percent. The Demon Deacons meanwhile shot 57.7 percent and turned an 11-point halftime lead into a blowout in the second half.

Foster battled valiantly through impaired vision in his damaged left eye, finishing with 19 points and 12 rebounds.

Despite a disappointing ending, the 1982-83 season was one to remember.

It was a season built in adversity, in which coach Bill Foster suffered a heart attack following a thrilling upset of No. 15 Purdue in December. The coach was sidelined for 17 games while recovering from quadruple bypass surgery.

Top assistant Steve Steinwedel led the Gamecocks to a 12-5 record during that stretch, including an upset of Idaho and a win over Georgia Tech, Bobby Cremins’ emotional return to Carolina Coliseum for the fist time as a head coach.

Late game heroics were commonplace; South Carolina won five games on last second shots, taking down four NCAA tournament-bound teams en route to the program’s most wins (22) since the 1973-74 season.

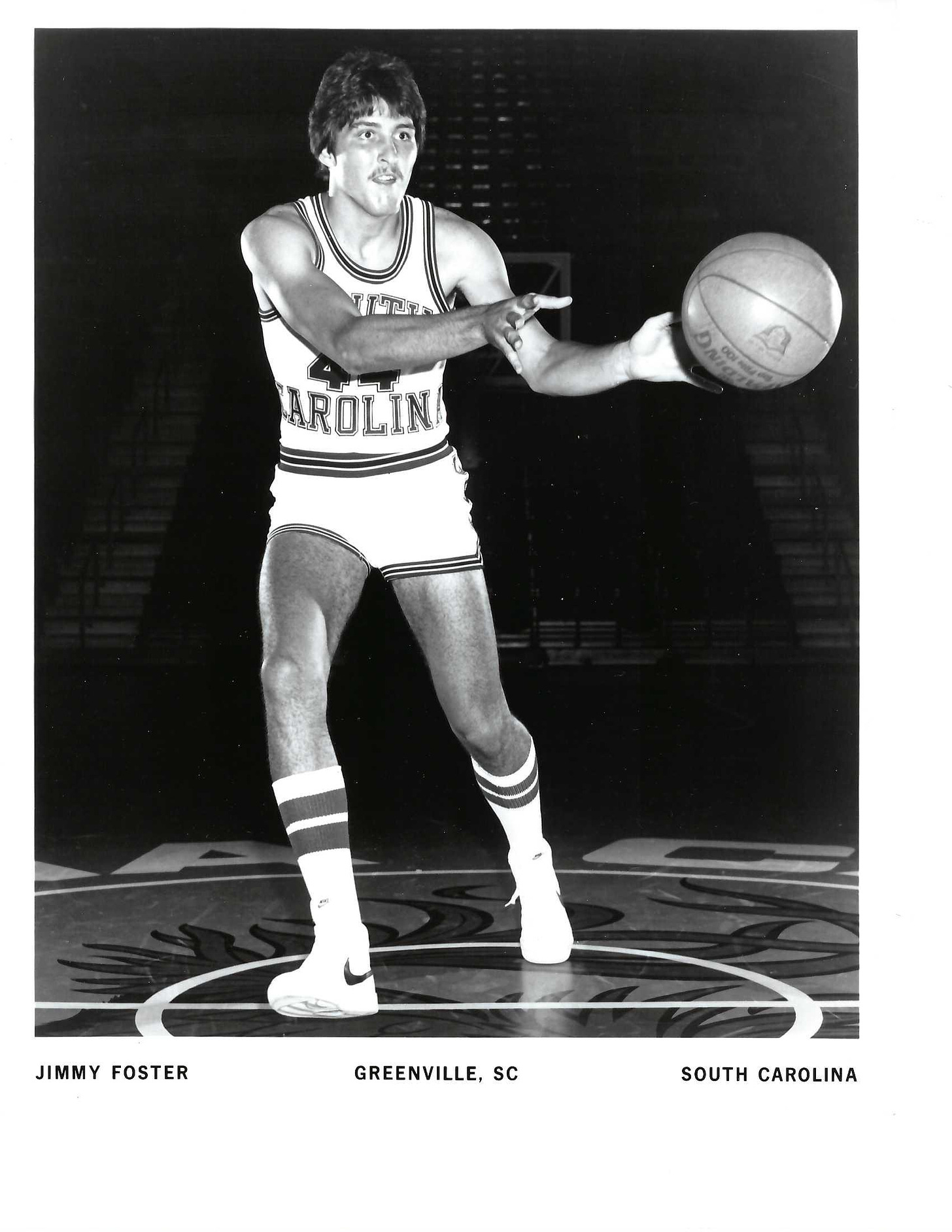

Despite losing team captain Gerald Peacock and forward Kevin Darmody to graduation, most of the Gamecocks’ production would return for the following season, including Foster, who once again led in scoring (17.3) and rebounding (8.9) as a junior. He also established a new school record for field goal percentage on the season (.611), which still stands today.

Foster was named Honorable Mention All-American and was a standout on the NIT all-star team which traveled to Australia over the summer. It would not be his last trip Down Under.

Despite a minor knee injury suffered during the tour which necessitated arthroscopic surgery, Foster returned at full health for his senior season.

After 12 seasons without a conference home, South Carolina began Metro Conference competition during the 1983-84 season. The new conference home seemed a move in the right direction for a program which had suffered declines in results and prominence since leaving the ACC.

Moreover, in recent years the NCAA had been trending toward awarding tournament bids to conference teams over independents, even those with better records, as South Carolina discovered in 1983. With a talented and experienced team returning and conference affiliation secured, all signs pointed to a brighter future for South Carolina basketball.

Bumpy final ride

While Foster’s senior season provided continued highlights to round out a superb career, team successes were rare. A pre-season academic casualty to key sixth man, senior Kenny Holmes and an unexpected medical redshirt for junior big man Duane Kendall were precursors of struggles to come.

“Expectations were big because of the success of the prior season, and then, all of a sudden Kenny wasn’t there, and it all started to unravel. (Bill) Foster was not as involved after the heart attack. (Assistant coach) Ray Jones was a recruiter, not much of a floor coach,” Foster said. “There was Steinwedel, but that season everybody was going in different directions. We had no common purpose, and that was reflected in the way we played.”

Indeed, personnel losses haunted the team, particularly the loss of Holmes, who possessed a deadly baseline jumper and was responsible for many of the last-second winning baskets in 1982-83.

Further, the loss of graduating point guard Peacock’s steady leadership and school record 182 assists was sorely missed, as the Gamecocks turned to freshman Michael Foster (no relation) to run the point. The younger Foster, a highly regarded talent from Greensboro’s Page High School, developed into a steady performer as the season wore on, but he was still a freshman cast into a difficult situation.

The Gamecocks struggled to a 12-16 record on the season, going 5-9 in Metro Conference play. After 15 consecutive winning seasons, the program had now suffered its second losing season in three years.

After a long season, Foster’s final home game provided a fitting finale for the blue-collar scrapper in the form of a 70-62 win over Southern Mississippi. With five seconds remaining in regulation and the Gamecocks comfortably ahead, Foster took a half court pass from fellow senior Scott Sanderson and went for a dunk attempt before being hammered by the Golden Eagles’ Kenny Siler.

A melee ensued between Foster and Southern Mississippi’s James Williams which spilled over into press row. Both benches cleared before Coliseum security eventually managed to break up the fight. As officials did their best to restore order, the pep band broke into a raucous war chant, shouting rhythmically, “Don’t mess with Jimmy, don’t mess with Jimmy!”

Paramedics took one spectator away after she was pressed against her seat by fans leaning forward to see the fight. Security ushered Siler to the visiting locker room as boos rained down, while Foster’s exit seconds later elicited a rafter-rattling standing ovation. It was drama fit for a Foster finale. He finished with 19 points and eight rebounds in another lunch pail performance.

South Carolina and Foster would lose their final two games: a nine-point loss at DePaul and a narrow seven-point defeat to Florida State in South Carolina’s first conference tournament game since 1971.

Foster finished the season averaging a career-high 18.5 points, adding 9.4 rebounds per game. He finished as the third-leading scorer in program history with 1,745 points.

His ten rebounds in the Metro tournament game gave him an even 1,000 career rebounds, one of only five Gamecocks to achieve that milestone. His .596 career field goal percentage still a program best.

A fleeting professional career

The Kansas City Kings selected Foster in the fifth round of the 1984 NBA draft, in the franchise’s final season before moving to Sacramento. In their draft analysis, The Sporting News compared Foster to the Lakers’ Kurt Rambis, the scrappy, blue-collar counterpoint to Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers.

The Kings ultimately released Foster, after which he played briefly in France before landing in Australia, where he signed with the Coburg Giants of the National Basketball League (NBL) prior to the 1986 season.

Foster played at a high level during his only full professional season. In his first game, he scored 43 points and collected 11 rebounds. During another, he netted a career high 50 points, adding 13 rebounds.

In Australia his game evolved, and he showed improved range away from the basket, including the occasional three point shot. His season average of 32.2 points and 11 rebounds per game earned him All-NBL First Team recognition. Much like his final college season, team success did not follow as the Giants finished 14-12, missing the postseason.

“Australia was good, but I had too much free time, which isn’t good for Jimmy Foster. I liked the fact that in college, our schedules were very regulated. There wasn’t a lot of time and that was good, at least for me,” Foster said. “Our home arena in Australia was next to a bar, and post-game meetings were held there. Teammates were smoking, drinking beers. That’s when I knew I was in a different place. It probably wasn’t conducive to what I needed at the time.“

“In college, it was fun. There was an us against the world mentality. We ate, slept and did everything together. In the pros, people had families and other commitments. They went their separate ways after practice and games,” Foster said. “And if you don’t win, the check still came on Friday. At the end of the game, if we lost, they didn’t want to sit and talk about how we lost, they wanted to go to the disco. It wasn’t what I was looking for. It wasn’t fun anymore. Once the desire was gone, that was that.”

Foster called it quits after one highly successful, if unsatisfying professional season. No doubt, one reason for his general sense of dissatisfaction was a series of events unfolding nearly 10,000 miles away in Columbia, which would alter his life and his relationship with the University of South Carolina.

The Dick Dyer Incident

Foster’s celebrity in the Columbia area was a key which opened many doors. He was handsome, with an easy smile and most who knew him described him as affable and popular. People wanted to be around him, to do things for him, to provide favors he was happy to accept.

These favors were not unique to Foster, nor were they unique to student athletes at USC. In many ways, the atmosphere surrounding major college athletics in the 1980s reflected the mores of society in general. For the best athletes, and those open to such things, the world was their oyster. As long as discretion ruled, the good times rolled.

In the summer of 1986, some of those chickens, or Gamecocks as it were, came home to roost.

Columbia-area Mercedes-Benz dealership Dick Dyer and Associates filed a complaint against Foster in August of 1985, alleging the former player borrowed a 1984 Mercedes 380 SL from them, promising to return it in three days.

Foster failed to return the car as agreed, and the vehicle was repossessed in Greenville several months later. Prosecutors subsequently filed charges against Foster and a trial was set for June 1986.

By the time of the trial, Foster was playing professional basketball in Australia. His attorney, Russ Templeton, told reporters he had not been in contact with Foster about the trial and his client would be unlikely to return for the court date.

Foster was tried in absentia and convicted by a Richland County jury of breach of trust with fraudulent intent, a felony, which carried a maximum penalty of ten years in prison.

The only witness called during the trial was David Thornton, a Dick Dyer sales associate. Thornton testified that Foster completed the paperwork to purchase, not borrow the car on June 26, 1985.

According to Thornton, Foster claimed his mother controlled his money, so he needed to take the car, valued at $36,000 ($96,000 adjusted), to Greensboro to show her in order to secure the funds for purchase. Foster, according to testimony, agreed to return to Columbia with those funds within three days.

Thornton testified that he agreed to release the car to due to Foster’s relationship with the dealership. Foster had borrowed cars on two previous occasions during his playing days at USC, and in both earlier instances, brought those cars back in time.

Despite Thornton’s testimony about completed sales paperwork, no documentary evidence was presented beyond Thornton’s telling.

Judge John Hamilton Smith issued a sealed sentence, which was to be opened when Foster returned to the United States, at which point he would be arrested.

Reached in Australia for comment by Dan Foster (no relation) of the Greenville News, Foster confirmed the loans, and also said he had used loaned cars from a Greenville dealership while a player at South Carolina.

Foster said Coach Bill Foster had been unaware of the loans, and he had no intention of harming the Gamecock basketball program. He stated further in the Greenville News interview that he did “not want to be the one to open the doors, but if I go down for this thing, I’m going to take a lot of people with me.”

A media frenzy followed over the coming weeks, as further revelations from Foster emerged about alleged improprieties both within the basketball program and by prominent boosters.

In a separate article several days later in the Columbia Record, Foster alleged he received gifts of cash, deals on loans, cars to drive, free meals at restaurants, and weekend trips to Myrtle Beach courtesy of boosters while a student-athlete at South Carolina. USC boosters “answered all of my wishes,” Foster said.

Foster pointed specifically to the DePaul game in 1983, a Gamecock win, saying an unknown booster shook his hand and handed him an envelope with ten $100 bills in it. A former girlfriend of Fosters, Susan Kensey, in an interview with the Hilton Head Island Packet, confirmed that story.

A few days later, yet another Foster allegation surfaced, this time concerning an operation overseen by a former Gamecock assistant basketball coach in which players were able to sell their ticket allotments to boosters for cash.

Players received four books of complimentary tickets for home games in those days, which they could distribute to friends and family. Those who participated in the scheme were alleged to receive as much as a 100 percent mark-up over face value. There was no direct interaction between players and boosters; the money went through the assistant coach.

Bill Foster had resigned as USC’s head coach following the 1985-86 season and by this time had taken the same position at Northwestern. Reached for comment in Chicago at the time, the former South Carolina coach denied knowledge of any of the allegations. Four other former Gamecock players, meanwhile, confirmed the ticket set-up, including Duane Kendall, and three other players who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Over a period of three weeks, Foster’s slow drip of allegations had unleashed three separate and distinct scandals on the Gamecock basketball program and the University of South Carolina. The allegations of borrowed cars, separate allegations of money, meals and favors from boosters, and the allegation of illicit sales of student-athlete tickets for profit, managed by an assistant coach.

It was the last allegation which attracted the attention of NCAA investigators. The University of South Carolina, under Athletics Director Bob Marcum launched its own investigation and cooperated fully with the NCAA.

On March 3, 1987, the NCAA’s Committee on Infractions announced the results of its investigation and the associated penalties for the South Carolina program. The violations revealed six findings, including:

· the loan/lease of cars to prospective athlete and enrolled student athletes;

· provision of transportation to or from Columbia at no cost for a prospective, and several enrolled athletes;

· short term lodging at no cost for several perspective athletes;

· provision of meals at no cost at several restaurants in Columbia;

· out-of-season practices in the summer and fall of 1984, involving prospective and enrolled student-athletes and men’s basketball coaching staff; and

· sale of student-athletes’ complimentary tickets by members of the men’s basketball coaching staff.

The report found that following Coach Bill Foster’s health issues in the wake of his heart attack in December 1982, he delegated much of the day-to-day operation and supervision of the Gamecock men’s basketball program to members of his staff.

During the 1984-85 academic year, the absence of institutional constraints permitted members of the basketball staff to engage in most of the violations reported to the committee.

The irony of the NCAA findings is that most, if not all occurred after Jimmy Foster had departed campus. No student-athletes or coaches were named in the NCAA report.

The NCAA imposed sanctions on the South Carolina basketball program, which included public reprimand and censure, a two-year probation period and postseason ban for the 1987-88 season. With Bill Foster now at Northwestern, new head basketball coach George Felton, a Gamecock letterman from the McGuire era, was left to deal with the aftermath.

“I drove their loaner cars for two of the four years I was at Carolina. I absolutely didn’t bring it back. I didn’t think it was a big deal at the time. So, I’ll plead to stupidity, or whatever. I don’t know how it got to that point. I wasn’t there at the time (of the trial). Maybe it was somebody seeing me drive a Mercedes around Greenville, and of course, it wasn’t like I didn’t want everybody to see me driving it around,” Foster said.

“I wasn’t the smartest, you know. I take all the responsibility. They probably intended to sell me the car, and they figured they could get me financed. They probably figured, ‘hey, he’s going go play (professional) basketball somewhere.’ But I kept it to the point where I think they realized they weren’t going to be able to get it financed, and that’s when they came and got it.”

Of the conviction and sealed sentence, Foster says: “I’m not sure if its settled or not. I’m pretty sure I’m not on the FBI’s most-wanted list. I don’t think anybody wanted to put Jimmy Foster in jail. I don’t think that was the point. I just think…I blew it. That’s what it came down to. I think it got to the point where they didn’t have any other place to go. I think if cooler heads had prevailed, mine especially; it wouldn’t have ended up like that. I have no idea what it (the sealed sentence) said. I would be curious to know. It may not even exist anymore if you tried to find it. I don’t think there’s anybody left alive that knows what it said.”

Fifth Circuit Solicitor, Jim Anders, now deceased, said in 1986 that he had placed notice of Foster’s legal status in the database of the National Crime Information Center, which would alert passport authorities to his fugitive status if he tried to enter the US. However, according to a Richland County Sheriff’s Department spokesman in 1987, the warrant was deleted from the database on December 24, 1986. “No one in this office deleted the warrant, and I don’t know who did”, the spokesman said.

The sealed sentence is another mystery. The State’s Bob Gillespie interviewed Richland County Clerk of Court Barbara Scott in in a June 1997 article about the sealed sentence. When Scott retrieved the sealed sentence from court archives, the envelope was open.

“The sentence is in there, but its no longer sealed”, she said. “There should be a record of why it was opened, but there’s no record. If it was never opened and published, it should still be sealed.”

Scott speculated the envelope could have been inadvertently opened, but as with many things with Foster’s story, time and uncertainty have obscured the details.

Years of rambling and regret

In 1987 a then-35-year-old Foster contacted The State’s Gillespie, saying his life had changed. He claimed to have a wife and a 10-month-old son, yet he said his fondest memories were his four years at USC.

He expressed regret for the lying and cheating, and the hurt he had caused family and friends. “I’ve got a lot of fences to mend,” he told Gillespie.

Of the bridges he burned in South Carolina by way of his allegations, Foster said previously, in 1986, that it didn’t matter to him. Because of the warrant awaiting him, he said he was planning to marry an Australian woman and become a citizen there.

But Foster told Gillespie that he never forgot South Carolina, and he expressed a desire to mend fences in Columbia.

“I’m not the same person I was then. I think I’ve matured,” he said. “I do realize I made a mistake. It was my fault. I implicated people. I didn’t make any friends. But I was cocky. I was in Australia. I didn’t think I wanted to come back.”

Foster lived a vagabond life for years, spending time in Southern California, Missouri, Montana and in the Wilmington, North Carolina area.

During my interviews, he shared a story of living for a time in Malibu, where “I was the only one living there that didn’t have any money.”

In a bar one night, he struck up a conversation with a local surfer. Foster had learned to surf, but joked “tall people are not conducive to surfing.”

After numerous drinks, the surfer offered Foster a place to stay for the night so he wouldn’t have to drive. A limousine was waiting for them as they walked out of the bar, which he says “impressed nobody, because everybody has a limo in Malibu.”

He continued, “The limo took us into the hills and to the gates of this mansion.”

After drinking late into the night, Foster settled into one of the many guest rooms saying “the next morning I was in the kitchen and I started looking at all these gold albums on the wall, and about that time, Olivia Newton John comes around the corner.”

The surfer, as it turned out, was Matt Lattanzi, Newton-John’s first husband. Foster said Newton-John “was polite, nice. She cooked us breakfast.”

He tells another story of befriending Martin and Charlie Sheen, who are avid basketball fans.

“They did their research. They knew I was who I said I was,” he said. “And I treated them just like regular people, and they wanted to spend time with me as much as I wanted to spend time with them.”

Foster describes these stories as “non-reality moments for a country boy like me.”

One could be forgiven for doubting the validity of these tales. He has been known to spin a yarn. But he tells them convincingly, off the cuff, with just enough obscurity in the details to ring true.

Peace in Northern California, and dreams of South Carolina

Foster now lives in Northern California. He drives an 18-wheeler, saying he finds satisfaction in the job. “It gives me a lot of time to be by myself and think.”

He says the materialistic tendencies of his youth, the desire to drive fancy cars, to see and be seen are long gone. He owns a simple cabin and drives an old pickup; an existence fitting for a guy nicknamed “Truck.”

The pace of Northern California suits him much better than the hustle and glitter of Southern California. There is a verdant natural beauty which reminds him of his native environs in the Carolina foothills.

He says now that he has never married and has no children. He has a girlfriend, he says, who keeps him on his toes, and who encouraged him to engage in these interviews.

He says he is at peace and, although he can’t do everything he used to do on the basketball court, he is in the best shape of his life. He plays a pick-up game from time to time. He still likes the feel of a basketball, still harbors that competitive fire.

From time to time over the years, he has driven through Columbia on the way to or from visiting his parents. He has on occasion stopped his car behind the Carolina Coliseum, along Park Street, where he used to enter the arena as a player.

“When I sit there and close my eyes, all the good memories come back,” Foster said.

He remembers the games, which he describes as “heaven,” the camaraderie with teammates, the feeling of being young and talented, with limitless possibilities.

When asked what he would say to former teammates and coaches, to fans, and the university community if given the opportunity, his answer was simple.

“Thanks for the best four years of my life. I’m sorry for the way it ended. I just want to be remembered for what I did on the court. I loved to entertain the crowd, and the fans drove me. I lived life like I played: my emotions on my sleeve. That had to be harnessed, and that took some time,” after a pause, adding, “I love the University of South Carolina”.

Final analysis

Like all of us, Jimmy Foster has made mistakes. Unlike most of us, his stage was a little bigger, the lights a little hotter, and the repercussions more severe.

Foster has paid a steep price for the mistakes he made as young man, spending the last 35 years, effectively shunned by his university and by a program to which he gave so much. He says the most disappointing part was when he didn’t receive an invitation to attend the Gamecock basketball 100th year celebration in 2008, saying that was “the most hurtful thing.”

Even so, he dreams of returning to Columbia, of a return to the program in some fashion.

He says he has no great desire to visit the “new place,” 20-year-old Colonial Life Arena, but would love nothing more than to walk through the old Coliseum, which he calls “Frank’s house,” where he spent so many of his younger days and nights.

Foster readily acknowledges his mistakes. And to be certain, the university is not blameless in the saga that is the Foster story.

One could argue it is time to leave those things in the past. That youthful indiscretions nearly four decades old could and should be set aside in the name of embracing one of the program’s very best.

As we approach spring, a season of renewal, and this year in particular a season of healing, perhaps this can be a time to bind up wounds rather than harboring old transgressions.

Foster turned 60 in January. For a long time he told those closest to him that he would never again discuss his days at the University of South Carolina. That changed. Time has a way of accomplishing things like that.