Assassination in a Southern Capital

James Tillman, N. G. Gonzales, and murder at Main & Gervais

Author’s note: While South by Southeast is primarily dedicated to the history of Gamecock athletics, I will indulge from time to time in other stories from the history of Columbia and the broader history of USC. Sunday, January 15, 2023 will mark the 120th anniversary of this notorious murder which has been widely forgotten with the passage of time. It is a nearly unbelievable tale of outlandish characters, toxic political rivalry, and cold-blooded retribution, which casts our current political tribulations into perspective.

“With the suddenness of a thunderclap from a cloudless sky, Tillman drew his weapon and sent the bullet on its deadly mission.” – The State, January 16, 1903

He almost forgot to eat sometimes. Such was the frenetic energy the editor poured into his duties at the newspaper he and his brothers founded over a decade before. This fateful day began no differently than most others, and none but one man could have predicted the sensational events which would unfold.

Friday, January 15, 1903 dawned seasonably cold in South Carolina’s capital city, with overnight lows around freezing. A weak winter sun brought temperatures into the 50’s by mid-afternoon as early clouds gave way to clear skies. Around 1:45 pm, Narciso Gener (N. G.) Gonzales, the 44-year-old co-founder and editor of The State newspaper stepped out of his office at 1220 Main Street, setting off on his customary one-mile walk for lunch at his home at 1010 Henderson Street.

Gonzales turned south on Main in the direction of the State Capitol building, which sat impressively helmeted under a new copper-plated dome added a year prior, now glittering in the afternoon sun. Bronze stars marked the chipped blue granite of the capitol’s western façade where Sherman’s cannons found their target from the Congaree River’s west bank some five decades before.

Fire from that march destroyed eighty-eight of Columbia’s one hundred and twelve city blocks on February 17, 1865 during the desperate, waning days of the Civil War. Char still colored the stone foundation walls of Main Street basements whose original buildings had succumbed to the conflagration, even after new structures were built atop, including the offices now home to The State.

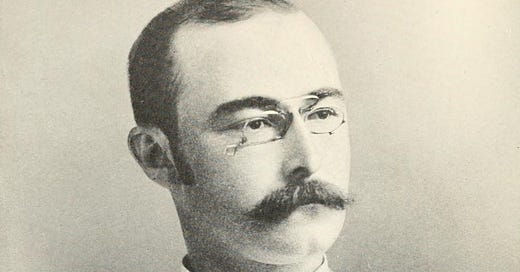

Gonzales had always been a man in a hurry. He was slightly built, with Pince-nez glasses, a chevron mustache, and twin crescents of scalp marking a hairline in steady retreat. His most distinguishing features were dark, piercing eyes, the windows into a searing intellect. Hands stuffed in overcoat pockets in his customary way, Gonzales strode with purpose the half block to Gervais Street, where he would turn east toward home.

Meanwhile, three legislators walked with equal purpose from the capitol building north, crossing Gervais, and meeting Gonzales just as he reached the corner. Within seconds the acrid smell of gunpowder filled the air, setting forth a chain of events which would shock the nation.

Amid a bustling capitol, the rise of “Tillmania”

Columbia boasted a population of over 26,000 residents by 1900, then the largest city in the Carolinas outside of Charleston. Commerce thrived along the city’s Main Street, originally Richardson Street, but renamed a decade prior to reflect its prominence. Still five years from being paved, Main Street, as all of Columbia’s grid of avenues, was a “miry bog,” as described by Charleston’s News & Courier. The bicycle craze of the 1890’s was still going strong, and “wheelmen,” were often pitted against walkers as they avoided muddy streets in favor of firmer, if more kinetic sidewalks.

The Gonzales brothers were the sons of a Cuban revolutionary, Ambrosio Jose Gonzales, and Harriett Rutledge Elliott, the daughter of a prominent South Carolina family. After living for a time in his native Cuba, Gonzales returned his family to his wife’s native South Carolina following Harriett’s untimely death.

Ben Tillman, of Edgefield County in the western part of the state meanwhile, was a former leader of the “Red Shirt” mob, purveyors of political violence, employing murder and mayhem to influence the 1876 Governor’s race. It was an election which effectively marked the end of Reconstruction-era Republican rule in South Carolina and the broader old Confederacy.

Following the election of 1876, the State Legislature closed the University of South Carolina to purge it of its Reconstruction-era influence. USC had been the only state-supported university in the South to accept and grant degrees to Black students. It reopened as the South Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanics in 1880, returned once again to an all-white institution.

Tillman later ran a virulently racist campaign for Governor in 1890, ridiculing the wealthy planter-class establishment leadership within the Democratic party, known as the “Bourbon Democrats,” led in South Carolina by former Confederate General Wade Hampton, III.

The Gonzales brothers, sympathetic by social standing and temperament to the establishment Bourbons, founded The State in 1891 primarily to oppose Tillman’s most nakedly demagogic impulses.

Tillman. popularly known as the “Agricultural Moses,” was both revered and reviled for his advocacy on behalf of an often marginalized agrarian and rural population. He listed among his 1890 reform platform a desire to permanently close the University of South Carolina, calling it the “seedbed of aristocracy.” (He also directed his ire at The Citadel, which he called a “dude factory”).

Tillman demanded reforms in higher education, reallocating funds from South Carolina College, as the institution was by then known, in favor of Clemson College, which had in 1889 been founded as the state’s agricultural college.

During Tillman’s inaugural speech on December 4, 1890, he called his election a “triumph of democracy and white supremacy over mongrelism and anarchy, of civilization over barbarism.”

Historian Lewis Pinckney Jones in Stormy Petrel, his 1973 history of N.G. Gonzales and The State, notes many of Tillman’s accomplishments were progressive, but his methods drove away many who might have otherwise been supportive but for the Governor’s combative style. He wrote:

“…his dictatorial, abrupt and profane actions and language alienated many of his own followers, and yet his demagoguery and appeal to the prejudices of the masses elicited the popular support necessary to keep him in office long enough to make many of his reforms a permanent part of the South Carolina body politic.”

Gonzales frequently skewered Tillman within the editorial columns of his paper, earning a reputation for acidity and sharp elbows. He called Tillman, “as promising a tyrant as was ever bred by a free republic,” among other less flattering screeds.

Tillman in return focused much of his significant ire upon Gonzales, to which N.G. quipped, “Governor Tillman is still advertising The State. We pay him nothing for doing it. It is a service of love.”

Tillman even propped up a rival Columbia daily newspaper, The Register, recruiting the agrarian agitator T. Larry Gantt as editor. Gantt frequently appeared, according to Jones, wearing a coarse woolen shirt with a soft collar and a “remnant of a tie.” His trousers stopped well above his worn brogans, and the tobacco in his long pipe was always supplemented by another wad in his cheek. Upon arriving from his native Georgia. Gantt reportedly warned Gonzales, “There’s no use for you fellows to begin telling lies, for I give you fair warning that I kin beat any man in South Carolina in the lying business.”

Gonzales called Gantt “Tillman’s salaried provocateur.”

Tillman easily won reelection in 1892, during a time when the governorship ran for a two-year term. Gonzales’ unrestrained attacks on Tillman, according to an early Tillman biographer, foolishly accentuated the division between businessmen and farmer, further endearing to the latter their iconoclastic leader.

Following Tillman’s second term, he ran a successful campaign for U.S. Senate in 1894. Tensions between Gonzales and Tillman settled into a relative ease back in South Carolina, with both men practicing a more restrained tone, and more moderate Reformers running the state. Soon after, a younger Tillman would disrupt that delicate détente.

“Tillman the Little”

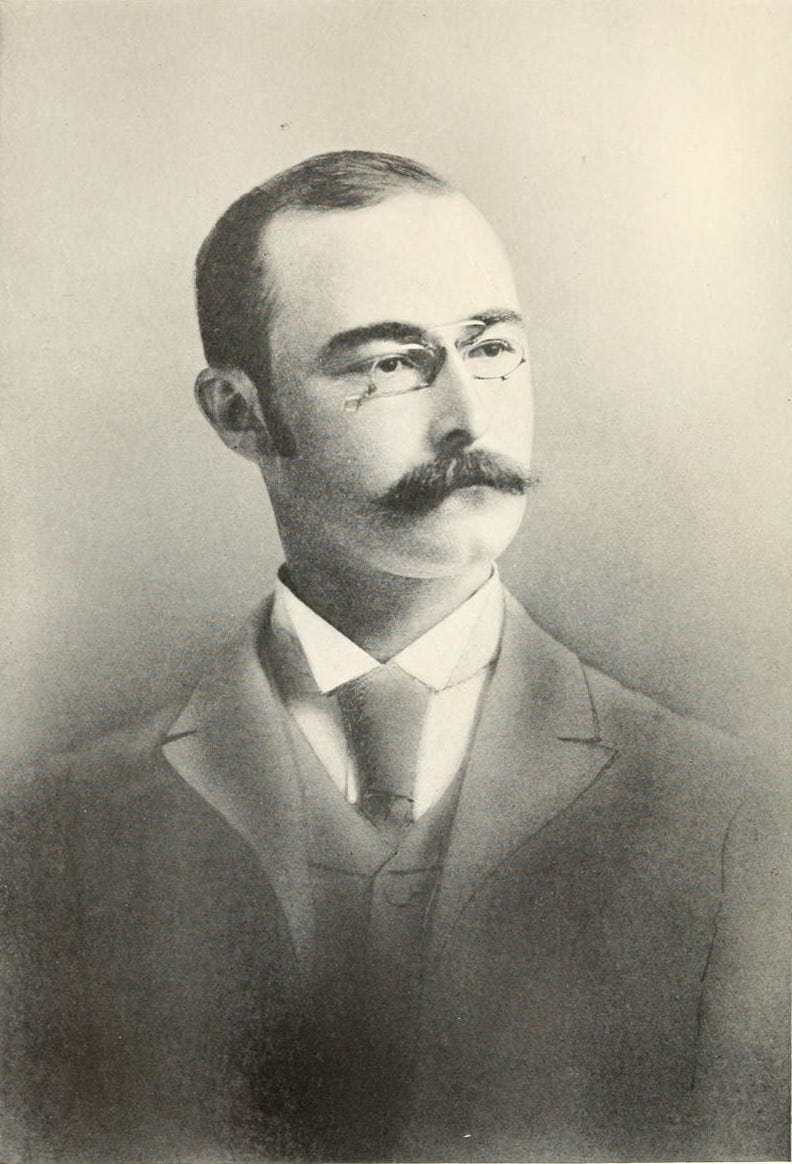

By 1900, Senator Ben Tillman’s nephew, James Hammond Tillman had risen, largely on the coattails of his famous uncle, to the position of Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina. When the younger Tillman announced his intentions to run for Governor during the 1902 election, Gonzales once again, “dipped his pen into the gall,” as Jones put it, calling Tillman among other things, a “debauchee,” a “blackguard,” and a “criminal.”

In a series of exposés, Gonzales documented Tillman’s falsifying of State Senate records and misuse of public funds, including the misappropriation of monies raised to construct a Confederate monument in his native Edgefield.

Jones wrote that the younger Tillman represented Tillmanism at its worst, noting that he “out-Tillmaned” his uncle as a master of demagoguery, particularly in arousing bitter anti-Black prejudices. “He was a known gambler, a drunkard, a ‘rascal’, and a free-spender of his and other people’s money.”

The feud between Gonzales and Jim Tillman actually went back to 1890, when an anonymous letter published in the Winnsboro News and Herald attacked Gonzales personally, describing him, among other racist tropes, as “a treacherous Spaniard.” Gonzales eventually discovered it had been James Tillman who wrote the letter, and he was later instrumental in blocking Tillman from attaining membership at a prominent social club in Columbia.

Following the second incident, Tillman sent Gonzales an “invitation to Georgia,” which was a thinly-veiled challenge to a duel. Dueling or challenging to a duel was illegal, explaining the awkwardly-worded invitation. “Georgia” was almost certainly a reference to an area where duels were sometimes fought on an island between South Carolina and Georgia. Gonzales declined the invitation.

Though Gonzales did not vigorously oppose Tillman’s run for Lieutenant Governor in 1900, writing, “we can stand it if the senate can,” things turned ugly a couple of years later, due to a series of high-profile events.

From December, 1901 to June, 1902, the City of Charleston hosted the cumbersomely-named South Carolina Interstate and West Indian Exposition, which aimed to improve trade relations between South Carolina, Latin America and Caribbean nations. A visit from President Theodore Roosevelt in April, 1902 highlighted the event. The Presidential visit, however, was nearly sidelined by poison politics.

Ahead of the President’s visit, James Tillman raised funds to purchase a sword for Major Micah Jenkins, a famed South Carolina military hero, and member of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. Roosevelt agreed to present the sword during his April visit.

The Presidential visit was endangered when on February 22, 1902, Ben Tillman and the Junior Senator from South Carolina, John McLaurin, engaged in fisticuffs on the floor of the U.S. Senate, sparked over political disagreements amid a pending vote on the annexation of the Philippine Islands.

McLaurin was an old mentee of Tillman’s going back years, but had been courted by Senate Republicans, and, likely motivated by a desire to see South Carolina participate more fully in the nation’s industrial progress. McLaurin turned away from his old mentor, infuriating Tillman.

During the annexation debate, Tillman charged with colorful language that McLaurin had succumbed to “improper influences,” in changing his position on Philippine annexation. McLaurin, who had been temporarily absent in committee meetings, got wind of the remarks and charged back into the Senate chamber to denounce Tillman’s diatribe as “a willful, malicious and deliberate lie.”

At that, the 54-year-old Tillman attacked the 41-year-old McLaurin. As Jones describes in Stormy Petrel, efforts to separate the two resulted in misdirected punches landing on other members.

The fight was the first in the Senate chamber since a similar incident fifty-two years prior, between Mississippi Senator Henry Foote and Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton on April 17, 1850, more than a decade before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Tillman and McLaurin were both found in contempt of the Senate, and both eventually offered apologies, though they each did so in such caustic terms that the ruckus threatened to explode once more.

This, and other outbursts on the Senate floor earned Tillman the nickname “Pitchfork Ben,” for his tendency to poke and prod political opponents, both verbally and at times, physically.

Following the censure of Tillman and McLaurin, the Senate passed Rule 19, a directive which prohibited senators from “directly or indirectly, by any form of words, impart to another senator any conduct or motive unworthy or unbecoming a senator.”

(In 2017, Republican senators used the arcane directive to sideline Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) after she cited criticism of then Senator Jeff Sessions (R-AL), President Donald Trump’s nominee for Attorney General. Warren quoted from a pair of letters written by the late Coretta Scott King opposing Sessions’ nomination to a federal judgeship in 1986, accusing Sessions of racial bias. Invocation of the rule silenced further comments from Warren until after Sessions’ nomination.)

Roosevelt subsequently cancelled an invitation for Ben Tillman to attend a White House dinner, after which James Tillman withdrew his invitation for Roosevelt to present the sword to Jenkins, the old Rough Rider. The unpleasant series of insults and disinvitations nearly sidelined Roosevelt’s Charleston visit altogether, but cooler heads eventually prevailed.

Gonzales, wrote of James Tillman’s insult to the President, “South Carolina is not responsible for this act of boorishness by ‘Tillman the Little.’” The State, in concert with several other dailies across South Carolina, raised money for a replacement sword, which President Roosevelt presented to Jenkins on April 9, 1902.

Amid these chaotic events, the younger Tillman entered the Governor’s race during the same month as Roosevelt’s South Carolina visit. Throughout the spring and summer of 1902, Gonzales was unrestrained in his open disdain and mockery of the younger Tillman, to the extent that his brothers and family friends warned him of the potential danger from Tillman, who was known to be violent. Gonzales responded that if Tillman were going to shoot him, he would have done so already.

Unlike Gonzales’ handling of the elder Tillman, there was no hint of humor or lampooning in his handling of James Tillman in the campaign of 1902. Gonzales noted there was no room to lampoon a man whose character offered no grounds for jest, noting also that, “compared to Jim, Ben was a gentleman and a patriot.”

Tillman ultimately finished fourth in the first Democratic gubernatorial primary on September 3, 1902. He bitterly blamed his dismal finish on Gonzales, citing the “brutal, false and malicious newspaper attacks” suffered at the hands of The State.

Though Gonzales no doubt took quiet satisfaction in the results of the election, his editorial guns went silent following the primary results, which denied Tillman a general election shot at the Governor’s Mansion.

For four and a half months, Gonzales turned his attention to other issues, while Tillman finished out his term as Lieutenant Governor and simmered over Gonzales’ role in his humiliating defeat.

“Shoot me again, you coward'‘

Gonzales and Tillman frequently crossed paths as Gonzales covered debates in the State House, and while walking upon the streets surrounding the capitol, always passing wordlessly, each careful to steer clear of the other.

As they both approached the corner of Gervais and Main Streets on that fateful day, Gonzales cut inside to make his left turn, putting him between Tillman and a trolly transfer building which then occupied the northeast corner of that intersection. Tillman was in the company of State Senators W. Brown of Darlington and Thomas Talbird of Beaufort.

As they came abreast, Tillman pulled out a large German Lugar automatic pistol to the surprise of his companions, and fired a shot which entered around Gonzales’ chest pocket, and exited with calamitous effect, bisecting his abdomen. The stunned Gonzales fell back against the transfer station and managed to push himself into a sitting position against the building’s south façade. As Gonzales stared up at his attacker, who stood with pistol drawn as if to fire a final deadly shot, the editor hissed, “Shoot me again, you coward.”

Tillman lowered his pistol and surrendered to Columbia policeman George Boland, who had been standing nearby. Boland found a second pistol on Tillman’s person.

One eyewitness to the event, Emma C. Melton, testified later that she was about to speak to Mr. Gonzales, whom she knew well. “His face,” she said, “was perfectly calm,” indicating that Gonzales was not anticipating trouble. Though the editor was known to own a revolver, he was unarmed at the time, a fact confirmed when the weapon was later found in a locked drawer at his desk.

Bystanders James F. Sims and Gamewell LaMotte went to Gonzales side, asking him where he wanted to go. He answered, “The State offices.” With Sims and LaMotte on either side, Gonzales struggled back to his office and was laid on the floor, his head propped atop a stack of newspapers. Doctors summoned to The State’s offices confirmed the situation was dire and Gonzales was soon transferred to the Columbia Hospital, “a trip he tolerated beautifully,” according to reports. As he was transported, Gonzales dictated his account of the shooting, which was later entered into evidence. An operation was performed in short order to repair the damaged intestines, and a colon which had been nearly severed by the bullet.

Word swiftly spread across South Carolina and beyond of the inconceivable shooting by South Carolina’s sitting Lieutenant Governor of its most prominent journalist. The focus of the entire city and state turned to Gonzales, and even Mrs. J. H. Tillman offered personal expressions of regret and sincere hopes of recovery to Mrs. Gonzales. Prayers were offered in churches throughout Columbia during services on Sunday, January 18.

Everywhere citizens gathered, talk centered around the sensational event. Reaction across the state was mixed, and fell along political lines, with many Tillman supporters perversely gleeful about the shooting and calling for immediate acquittal. To many, the surprise was not that Gonzales had been shot, but that it had not happened months earlier, in the immediate aftermath of Tillman’s primary loss. As one editorial put it, according to Jones, “If a man insists upon playing with live wires, electrocution generally results. Nonetheless, it is a great pity.”

Despite the best efforts of Columbia’s most esteemed surgeons, Gonzales’ wound proved mortal, as medical practices of the day were not sufficient to repair the damage and reverse the effects of Gonzales’ extensive blood loss. By Wednesday, January 19, the 44-year-old Gonzales succumbed to peritonitis, a septic inflammation of his ruptured colon.

News of Gonzales’ death unleashed a spasm of grief and rage among editors, who swiftly elevated him to a martyr for the freedom of the press. Telegrams offering expressions of sympathy from all corners of South Carolina, and from as far away as New York and San Francisco flooded the offices of The State. A representative message sent from C. A. Matthews of Charlotte in the hours before Gonzales’ death read, “Give my love to your brother and tell him Charlotte feels deeply for him in his sufferings. May God spare him to The State and to South Carolina.”

The “Trial of the Century”

South Carolina’s Chief Justice Young L. Pope refused Tillman bail in the days following the murder. Though confined in the Columbia jail, Tillman received hundreds of well-wishers at his cell who came bearing gifts of furniture, books, and flowers.

In the murder trial which followed, Solicitor William Thurmond, father of future Governor and U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond, received the assignment to prosecute Tillman. The Thurmond family, as the Tillmans, had deep roots in Edgefield County.

Defense council opened by filing for a change of venue when hearings began in June, 1903. The defense introduced hundreds of affidavits to demonstrate that Tillman could not receive a fair trial in Columbia, the home of Gonzales’ State, where local sentiment was stridently anti-Tillman, and where a monument to honor the fallen editor was being planned.

The court agreed to move the trial to neighboring Lexington County, which was notably more rural and historically voted more overwhelmingly for Ben Tillman than any other county, including Edgefield.

The State hired a young stenographer, James F. Byrnes, to record trial proceedings for its columns. In later years, Byrnes would serve as South Carolina Governor, U.S. Senator, Supreme Court Justice, and the 49th Secretary of State under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Ben Tillman largely avoided the trial, appearing in the courtroom just one day, but offered support in helping to arrange legal counsel. Though he had for years distanced himself from James, he noted, “Jim Tillman is my nephew, and blood is thicker than water.”

A special train operated daily during the three-week trial, carrying the many reporters and interested spectators the twelve miles between Columbia and the Lexington County Courthouse. Beyond The State’s stenographer Byrnes, reporters from the Anderson Daily Mail, the Charleston Evening Post, Florence’s Daily Times, Greenville’s Daily News, Spartanburg’s Daily Herald, Greenwood’s Daily Index, and Sumter’s Daily Item provided extensive coverage, along with representatives from other regional and national outlets.

The defense team had little with which to work. Tillman, after all, admittedly shot the deceased in broad daylight at the most prominent intersection in Columbia, an event witnessed by dozens. During the trial, Tillman’s counsel argued that the defendant shot Gonzales in self-defense, having seen Gonzales’ hands in his coat pockets, and claiming one of them “moved menacingly.” Perhaps unsure of the convincing power of their “menacing hands” defense, Tillman’s attorneys also introduced a number of inflammatory editorials penned by Gonzales as evidence that homicide was justified.

The prosecution, led by Thurmond, countered with testimony that Gonzales was known to walk unarmed, and had frequently passed Tillman in the street without incident. Further, they argued, “thumb wriggling” was no justification for murder.

Many editorials introduced by the defense were shown by prosecutors to be quotations from other newspapers. Twelve of the thirteen dailies in South Carolina, ran frequent anti-Tillman editorials during the 1902 election. Yet, assistant prosecutor William Elliott noted, The State was the most prominent, and Tillman’s defense team “placed the abuse of every newspaper… upon the head of Gonzales.”

The prosecution showed that Tillman had never even contemplated the possibility of a lawsuit against Gonzales for the editorial attacks his lawyers claimed were so provocative and libelous. Further, the State produced witnesses who testified that on several occasions during the 1902 campaign, Tillman commented that he ought to murder Gonzales.

William Elliott closed for the prosecution by saying a verdict of “not-guilty” would mean no less than an end to freedom of the press, adding that the defendant had, “slain the prosecuting witness, and added a crime to his record which far exceeds anything charged against him by the dead editor. James H. Tillman’s motive was revenge, and he is a murderer.”

Despite an airtight prosecution and a shaky defense, friendly Lexington County jurors acquitted Tillman, bringing a shocking end to the three-week trial. Following the verdict, The State dropped its policy of neutrality, in place since the shooting, proclaiming in bold headlines the next day, “THE FARCE IS ENDED…. THE CARDS WERE STACKED.”

According to Jones, both pulpit and press roundly condemned the verdict as a travesty in the days which followed. Fund raising for a monument to honor Gonzales, which had been paused during the trial resumed in earnest.

Tillman retired from public life following the trial, disgraced and in poor health. He died at the age of 42 in Asheville, North Carolina on April 11, 1911.

An often-forgotten monument stands watch over lawmakers still

On December 12, 1905, a granite obelisk was unveiled before an estimated crowd of 2,000 at the corner of Sumter Street and the eastern terminus of Senate Street across from the State Capitol complex. The location marks the route which Gonzales walked daily between work and home.

Josephus Daniels of the Raleigh News & Observer lauded his peer on the occasion, noting, “He was simply an editor in a small Southern capital, who made a great newspaper simply through his ability and his pluck. The people of South Carolina erected a monument to that editor because he fought their battle and because he was the foe to public men who do not have the high conception of public office as a sacred trust.”

Among the etched tributes is a quote from Gonzales’ own December 10, 1900 editorial in The State, which notes, “The measurement of success is not what we get out of life, but what we leave after it.”

Sources

· Lewis Pinckney Jones, Stormy Petrel: N.G. Gonzales and His State, Columbia, S.C., University of South Carolina Press, 1973.

· S.L. Latimer, Jr, The Story of The State and The Gonzales Brothers, Columbia, S.C., The State Printing Company, 1970.

· James Howell Underwood, Deadly Censorship, Columbia, S.C., University of South Carolina Press, 2013.

· Andrew Glass, “Senate Witnesses a Fistfight, February 22, 1902,” Politico, February 22, 2017.

Mr. Piercy, with this post and many others like it--reminds me of a quote ascribed to, one, Winston Churchill--that went something like this " the farther backward you can look, the farther forward you can see!"

During this disputatious time we all find ourselves in--the relevance of this quote--allows me to see farther into these coming years! And what I see in the 'short time'---- 'farther forward' is as dystopian as I can recall ever seeing.

Great retelling of an important part of the history of South Carolina. Resonates well in the divided, emotionally charged, modern political environment. Had always known some of the story, but this filled in important details and connections to later political figures and events. Sharpens the distinctions between geographical areas of SC and its institutions. Thank you for the story.