A conversation with Jimmy Graziano

McGuire-era big man talks about Gamecock basketball and life

The phone rang in Jimmy Graziano’s boyhood home at 17 Dolphin Drive in Farmingdale, New York in the summer of 1974. The male caller asked to speak with Jimmy, who was then out of the house. Graziano’s mother, Nadja, asked if she could take a message, to which the man replied, “This is Frank Sinatra.” The quick-witted Nadja replied, “and I’m Ella Fitzgerald” as she hung up the phone.

Sinatra’s assistant quickly called back, convincing Nadja of the authenticity of the call, and in short order set a meeting between young Jimmy and Ol’ Blue Eyes in New York, and later, Las Vegas.

Sinatra, as it turned out, was lending his voice and influence to the recruiting efforts of good friend and UNLV head coach, Jerry Tarkanian. Graziano was a hotly-recruited six-nine center prepping for his junior season at Farmingdale High School, and was on the radar of major programs across the country that summer.

Graziano humored Sinatra with the visits, but in a 2016 You Tube interview, said he never wanted to go to UNLV. “I wanted to write,” Graziano explains, I wanted to do some other things [besides basketball], I wanted to get into journalism, so I said “no thank you.”

Heavy on Graziano’s trail that summer was another influential New Yorker, the University of South Carolina’s legendary coach, Frank McGuire. Graziano relays a story about Sinatra who was having dinner at Jimmy Weston’s, a famous Manhattan social club which drew big names from New York’s sports and entertainment worlds like moths to a flame in the 1970’s. Weston, the gregarious club owner was known to bear hug regulars and pilgrims alike, often breaking into a soft-shoe shuffle when the in-house jazz band hit its stride. He was a close associate of both Sinatra and McGuire.

As Sinatra was walking out of the restaurant one evening he saw an oil painting of Frank McGuire at the entrance. Sinatra walked over to the painting, took it off the wall, and said over his shoulder to no one in particular, “You can have Graziano, but I’m taking Frank’s picture.” Sinatra loaded the McGuire painting into his limousine and disappeared into the Manhattan evening.

McGuire’s storied NYC recruiting pipeline delivers once again

Indeed, Graziano chose McGuire and the Gamecocks, and it was a huge pick-up for the program. South Carolina entered the 1976-77 season without the services of two program greats, in all-time leading scorer Alex English, and floor general Mike Dunleavy, who added 1,586 career points to English’s 1,972 over a largely successful four-year period during which the Gamecocks compiled 81 wins against 30 losses, including one Sweet Sixteen finish in two NCAA tournament appearances, and an NIT.

With English and Dunleavy lost to graduation, McGuire’s program found itself at a crossroads.

The 1975-76 squad finished 18-9, the tenth consecutive winning season under McGuire, but for the first time in six years, there was no NCAA or NIT invitation awaiting the Gamecocks at season’s end. South Carolina had by then completed five seasons of competition as a major independent since departing the Atlantic Coast Conference.

Beyond missing the post-season the specter of a sustained decline was spreading slow and steady like kudzu vines around the once elite program. Average attendance at the eight-year-old Carolina Coliseum, had dipped below the 10,000 mark for the first time ever in ‘75-76, to 8,988 per game. Though McGuire himself was still revered in Columbia, enthusiasm for the program itself was, perhaps unavoidably, beginning to slip the absence of those heated ACC rivalries.

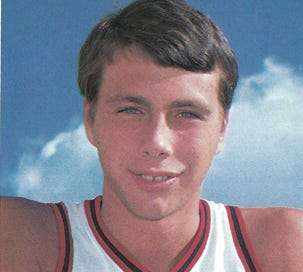

Despite troubling trends, McGuire and his top assistant, Donnie Walsh showed they could still attract top talent when the pride of Farmingdale, New York committed to the Gamecocks. Graziano had been voted one of the top five high school players in the nation when he averaged 22 points and 15 rebounds during a senior season in which he earned his second-consecutive high school All-America recognition. He also earned a spot on Sport Magazine’s “Dream Team” of prep players across the country.

Of his interest in coming to South Carolina, Graziano explains,

“When I was a youngster, South Carolina basketball was pretty important because there were a lot of guys who came from the area that we all followed - Kevin Joyce, Brian Winters, John Roche, Tommy Owens, and some other guys who went down there and were very successful from the New York City area. I had been following them as a kid.”

Graziano says he, along with guard Mike O’Koren of Jersey City, and six-eleven center Mike Giminski from Monroe, Connecticut visited USC, North Carolina, and Duke together. “We were all fairly close. We played in a lot of games together [in high school].”

Giminski ultimately chose Duke, then coached by Bill Foster, who would in four years replace McGuire at South Carolina. He went on to a sterling career as a Blue Devil, departing Durham in 1980 as the program’s leading scorer and a first round draft pick of the NBA’s New Jersey Nets. O’Koren chose UNC where he enjoyed a stellar career under the tutelage of legendary coach Dean Smith, and like Giminski, was a first-round draft pick of the Nets in 1980.

Graziano meanwhile, chose South Carolina, and arrived in Columbia along with a freshman class that also included forwards Mark Connaughton of Cincinnati, Carlton Hilton of Norfolk, Virginia, and guards Mike Doyle of the Bronx and Kenny Reynolds from Brooklyn.

They joined a nucleus of returnees highlighted by six-four forward Nate Davis, a senior from Columbia’s Eau Claire high school. A phenomenal athlete and prolific scorer, Davis was named captain for the ‘76-77 squad. Complementing Davis was a steady producing six-five forward from Columbia’s Keenan High School, Golie Augustus. Feeding Davis and Augustus the ball more often than not, was a six-foot ball-handling whiz from West New York, New Jersey, Jackie Gilloon, whose career assist average of 5.08 per game still stands as a program record. A duo of seniors rounded out the bulk of McGuire’s returnees, in big man Chuck Sherwood and swingman Stu Klitenic.

Though the Gamecocks of 1976-77 produced mixed results in the win-loss column, struggling to a 5-9 record over the first fourteen games, there were some glimmers of hope. Carolina performed valiantly during a four-point home loss to top-ranked Michigan on January 2, the Gamecocks’ fourth top-five opponent in three weeks. A month later, the team continued to gel, compiling a six-game win streak capped by an 85-66 win over The Citadel on February 9. The win provided McGuire his milestone 500th career victory en route to a winning 14-12 final record.

Celebrations and honors followed for McGuire, including induction into the Naismith Hall of Fame and a lavish black-tie appreciation banquet at the Carolina Coliseum in March of ‘77 which attracted a who’s who of former players, fellow coaches, and celebrities from the sports, entertainment, and political worlds who descended upon Columbia to fete the legendary Irishman. It was an accomplishment that solidified McGuire’s standing in the basketball world, and allowed his current squad to enjoy the reflected glory of teams past. In April of that year, USC officials rededicated the arena portion of Carolina Coliseum as “Frank McGuire Arena,”

Graziano enjoyed an outstanding freshman campaign, finishing second on the team in scoring with 13.2 points per game behind only Davis’ team-leading 15.7. Graziano also matched Davis’ 7.7 rebounds per game for tops on the team. He says of his first year in at Carolina, “It was a great year for me and I really liked the program. All the guys became close. We had seniors that really cared about everybody else in Nate Davis and Chucky Sherwood.”

Coaching change foreshadows tough times

Before the start of the 1977-78 season, McGuire’s long-time associate head coach Walsh left for an assistant coaching position with the NBA’s Denver Nuggets under coach Larry Brown. Walsh and Brown had been teammates and good friends, playing for McGuire at UNC in the early 1960’s.

Graziano recalls walking into the locker room in February of ‘77, shortly before the end of the season and seeing Brown. “I said to myself ‘what the hell is Larry Brown doing in our locker room?’ I didn’t understand his association with Donnie at all. And then I later came to the realization that he [Brown] had come there to ask Donnie to join him with the Nuggets.”

Walsh had served for twelve seasons as McGuire’s top assistant, and for many years appeared to be the heir apparent to McGuire at South Carolina.

“Donnie was the one who recruited me and I kind of went there [USC] because of Donnie, and still to this day have great admiration for him. And he did a lot for me when I was down there in my freshman year. He would say ‘be on the court 30 minutes before every practice,’ and we would go down to one basket and he would work with me on big man drills, and really worked me very hard, and I really liked Donnie and bought into the program.

Graziano continues,

“He was the associate head coach on paper, but he pretty much did seventy or eighty percent of the coaching at our practices. McGuire would sit about halfway up the stands in the Coliseum with his bullhorn, and every once in a while, he’d scream out, ‘Graziano, you stupid fuck! Throw the ball with two hands! You can’t throw the ball with one hand!’”

Things changed dramatically within the program and for Graziano following Walsh’s departure. Assistant coach Ben Jobe, a former head man at South Carolina State, was tabbed by McGuire for the head assistant role. Former Gamecock great Kevin Joyce joined McGuire’s staff as an assistant after his professional career was cut short due to a knee injury.

In short order, Jobe and McGuire landed commitments from a trio of transfer big men who would eventually challenge Graziano for playing time. Cedric Hordges, a bruising six-eight, 230-pound power forward from Montgomery, Alabama transferred from Auburn; Tom Wimbush, a six-six forward who also hailed from Montgomery, transferred from Anderson Junior College (now Anderson University); and Jim Strickland, a six-eleven center who prepped at Columbia’s Keenan High School transferred from Furman University. Though they would have to sit out the 1977-78 season due to NCAA transfer rules then in place, they would each have two seasons of eligibility beginning with the 1978-79 season.

Graziano says he was approached about transferring, namely by a young Rick Pitino, then at Boston University. “He called and said, ‘listen, come up here, get out of that. It’s not gonna end well for you.’ And of course, I didn’t listen. [I] ended up staying there,” Graziano continues, “and I had a pretty good sophomore year. We ended up going to the NIT and we got knocked out in the first round by North Carolina State. But that was probably our best year in the four years [I was] there,” Graziano reflects on the Gamecocks’ 16-12 campaign.

Though not as productive as his freshman campaign, Graziano played well again as a sophomore, averaging 10.4 points per game, good for fourth on the team, while leading the squad once again with 7.6 rebounds per contest.

Through two seasons, Graziano had compiled 633 points and 414 rebounds, placing him on par with some of the best to wear garnet and black. The thousand-point career threshold was well within reach, and with some luck, maybe the thousand-rebound threshold too. He was one of two returning starters for 1978-79, along with the Gamecocks’ floor general, Doyle.

Injuries and elevated competition at the post ultimately combined to frustrate Graziano during his final two seasons. His scoring average dipped to 3.9 as a junior before bottoming out at 2.4 points per game as a senior. His 31 total points during his senior campaign of 1979-80 was ninth on the team, playing in just fourteen games, starting one.

Meanwhile, Hordges, Strickland and Wimbush combined for 34.1 and 38.1 points per game in 1978-79 and 1979-80 respectively, and dominated playing time in the paint for McGuire’s Gamecocks over that two-season span.

It was a disappointing end to a promising collegiate career. Graziano’s struggles mirrored those of his coach. As wins and attendance diminished in the late 70’s, the political winds shifted for McGuire with a new university president, Jim Holderman, and a new athletics director in head football coach Jim Carlen, with whom McGuire squabbled publicly on occasion.

One-time allies soured on McGuire as well, namely South Carolina’s Speaker of the House emeritus, Solomon Blatt, Sr, whose grandson, Gregg was a one-time assistant under McGuire. When Walsh departed, rumors surfaced that Blatt pressured McGuire to name Greg his top assistant. When McGuire named Jobe to the post instead, Blatt, Sr’s bitter disappointment led to a widely-rumored campaign to reassign McGuire within the university system, and when that did not work, a forced retirement due to age.

Fans, students, and players rallied with highly vocal support for McGuire who ultimately survived those efforts and completed his contract which expired following the 1979-80 campaign. However, the final two seasons were decidedly turbulent ones for McGuire and his program.

Better days in Europe

Graziano was drafted by the Denver Nuggets following his disappointing senior season. “I think Donnie drafted me out of pity in the 9th round in 1980,” Graziano says with amusement now. He was ultimately cut from the team, and returned to USC to finish his remaining nine credits, graduating in December, 1980. From there, it was onto Europe to reclaim his floundering basketball career.

“I ended up going to Scotland of all places. I got [the equivalent of] fifty dollars per week, and they gave me a job in a soda bottle factory,” Graziano laughs before continuing, “I was really down after what had happened in, ‘78, ‘79, ‘80, and then slowly fought my way back from there. I had a really good season in Scotland.”

Graziano played half of the next season in Chile before making his way back to Europe, playing in Belgium, then ultimately landing in France by 1983. “We ended up doing pretty well, and [I] stayed in France for thirteen years. [I] raised three kids, three daughters who absolutely turned out fabulous.”

Following a lengthy and rewarding playing career, Graziano retired from basketball in 1996, settling in Bordeaux where he transitioned into teaching English, focusing primarily on helping recent immigrants. “I fell in love with ESL (English as a Second Language), and I think probably next to basketball, that’s been the second biggest love of my life… its very, very satisfying.”

Of his years in France, Graziano is filled with gratitude.

“I got a chance to see a lot and learn a lot, and to be able to speak a second language fluently. I never had a career in the NBA, but what I got out of it [basketball], I mean, it took me to another country, it introduced me to another civilization, and just to be able to take my wife back to France and go through some of those gorgeous valleys and chateaus. It’s just absolutely stunning.”

Now a dual US and French citizen, Graziano returned to the US in 2006. Soon after, he married his second wife, Laura. Now 66 and living just a few miles away from his boyhood home in Farmingdale on Long Island, Graziano still actively teaches ESL, and runs a basketball training camp when facilities are available.

All these years later, he remains immersed in teaching his two great loves, basketball and language.

It has been nearly forty-four years since he played his final game in garnet and black, but the memories linger, the feelings come rushing back. “I still love Columbia. I still love South Carolina. I was there in February [2023], I was there when they had the 100th anniversary of Carolina basketball [in 2003]. I have a lot of good friends down there still, and the program is great. I mean it’s great what Frank Martin did with the Final Four.”

Something tells me he would be pretty jazzed about second-year coach Lamont Paris as well, and the Gamecocks’ sizzling 13-1 start to the 2023-24 season.

Graziano was perhaps the last great recruit delivered by the old McGuire pipeline from New York City to the Carolinas throughout the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s. He followed a long line of flinty Gotham ballers whose retired jerseys still haunt the rafters in Chapel Hill and Columbia. Though fate’s plan did not allow his number 31 jersey to join them in that rarified air, dusty media guides and old newspaper clippings still bear witness to just how good he was when he was at his best.

Frank Sinatra knew it. His impromptu larceny of a McGuire oil painting tells you all you need to know about that.

Alan, I am more and more impressed about how you can capture a time in South Carolina Sports in such fluid, succinct and elaborate detail. Thank you!

Great article. Graz was the man. Anyone know where Steve Harty is these days ? He was on the Gamecocks squad with him.